Their struggle is not with creativity, but with access. They can weave magic with their hands, but they lack a platform — a place to reach customers directly. Most of their earnings are eaten up by middlemen and wholesalers who buy at low prices and sell at high margins elsewhere.

The handloom industry is one of India’s oldest and most soulful crafts, a living bridge between the past and the present. Across the country, millions of weavers spin not just fabric, but heritage itself. In Bihar, this legacy thrives quietly through clusters in Bhagalpur, Gaya, and Nalanda, where generations of artisans have devoted their lives to the loom.

Bihar’s handloom weaving has a long history, dating back to the Mauryan and Gupta periods. The state’s famous Tussar and Mulberry silk once travelled through old trade routes, adorning royal courts and temples. Bhagalpur, known as the ‘Silk City,’ became the centre of this craft, while Nalanda and Gaya developed cotton and silk-blend weaving traditions. Over generations, weaving turned into a family skill, with designs inspired by nature, festivals, and local life.

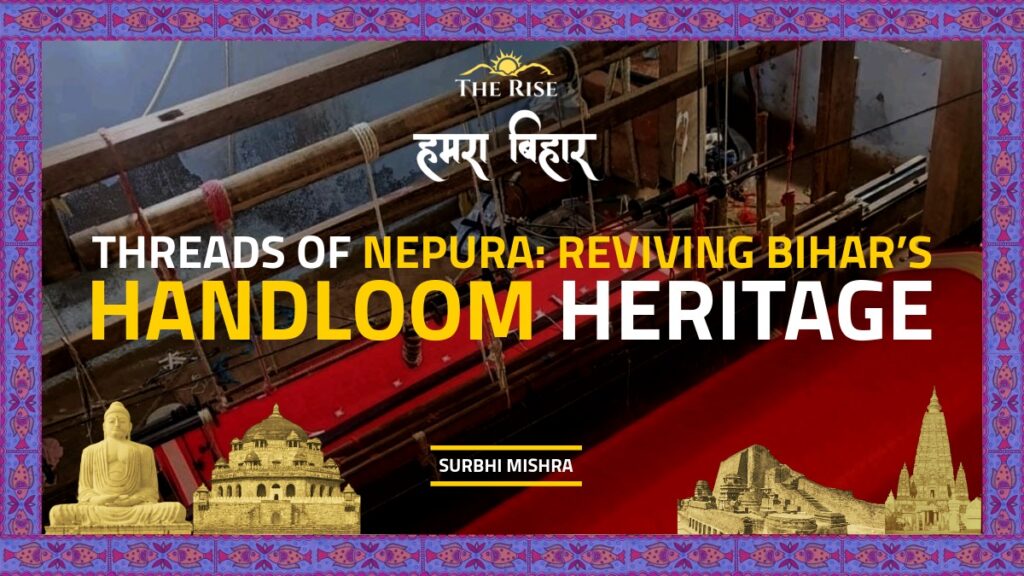

The weaving process is simple but skilled. It starts with silk cocoons that are reeled into fine threads, dyed with natural colours like turmeric, indigo, and pomegranate rind, and woven by hand on wooden looms. But over the years, powerlooms and machines have replaced many handlooms, producing cloth faster and at lower cost. With synthetic fabrics and mass-produced garments taking over, the demand for handwoven textiles has sharply declined, leaving traditional weavers struggling to sustain their livelihood.

Even as economic struggles and limited government support threaten its survival, Bihar’s weavers continue to keep this age-old tradition alive. It was in this spirit that TheRise visited Nepura village, situated between Nalanda and Silao, a region quietly known for its handloom silk and cotton weaving. What emerged there was not merely an industry, but a living tradition: a community where almost every household is connected by threads of silk, cotton, and patience.

Walking through the narrow lanes of Nepura, the rhythmic ‘tak-tak’ of wooden looms filled the air. Inside small mud-brick homes, men and women sat by their looms, their hands moving in practiced harmony.

“We may not have machines, but we have skills and soul,” said Rajendra Prasad, one of the respected weavers of the village. These silk cocoons are sourced from Gaya and Bhagalpur. The threads are then carefully reeled and dyed using natural colors, and then handwoven on these looms.

“Each saree takes ten to fifteen days,” said Shanti Devi, who has spent nearly 15 years at the loom, showing the fine threads of silk and cotton, explaining how intricate her job is. “We weave from memory — no prints, no machines. Every pattern is ours,” she further added.

Nearly every family in Nepura is engaged in weaving, yet most live on modest means. The average cost of producing a single handwoven saree can be around ₹2,200, but the artisans often have to sell it for just ₹2,300–₹2,400, earning a meagre ₹100–₹200 profit margin.

“It hurts!” said Ramesh. “The work is pure art, but we are forced to sell it cheaply just to keep going.”

What makes it even harder is that the earnings rarely reflect the labour behind each piece. In most households, several family members — from women who spin and dye threads to children who help with reeling and finishing — contribute to the process, yet payment is usually made in the name of just one person. This not only reduces the overall income but also hides the invisible labour of women and younger members.

“The saree may carry my husband’s name,” said Shanti Devi, “but every thread has our family’s effort in it. We all work, but the pay never shows that,” she further added.

Their struggle is not with creativity, but with access. They can weave magic with their hands, but they lack a platform — a place to reach customers directly. Most of their earnings are eaten up by middlemen and wholesalers who buy at low prices and sell at high margins elsewhere. To increase their margin, these weavers have now started to create a mix of silk and cotton fabrics, crafting sarees, suits, bedsheets, and sustainable clothing that combine comfort with elegance.

What makes Nepura’s weaving special is its deep connection with sustainability. The silk and cotton are locally sourced. This reduces transport costs and supports nearby farmers. Natural dyes ensure eco-friendly production, and the handlooms require no electricity, keeping the carbon footprint minimal.

“People talk about sustainable business now,” said Rajendra with a gentle smile. “But for us, this is not new — this is how our fathers and grandfathers lived.” Each finished product, whether a silk saree or a cotton bedsheet, carries not just craftsmanship, but also conscience. It’s local, ethical, and beautifully human.

Across the world, Indian handloom fabrics are now being celebrated as luxury products of authenticity and sustainability. Designers in Paris, Tokyo, and New York have showcased Indian silks for their raw, handmade beauty. Yet, the weavers of Nepura remain far from this global spotlight.

“A Japanese buyer once told me our silk feels like the soil of India — real and rooted,” recalled Rajendra. “But for that to mean something to us, we need fair markets and buyers who understand our worth.”

The irony is stark — while global demand for ethical and handmade fashion is rising, artisans like those in Nepura continue to struggle for recognition and fair prices at home. Their work, though celebrated abroad, remains undervalued in local markets, where middlemen and low margins dictate their earnings.

Recognising this gap between appreciation and access, the Indian government in recent years has introduced several initiatives to revive and support the handloom sector. These include the National Handloom Development Programme (NHDP), Silk Samagra, and the Handloom Mark Scheme, all designed to improve production, skill development, and marketing opportunities for weavers.

In Bihar, these efforts have translated into training camps, design workshops, and local exhibitions organised by the Bihar government. Some families in Nepura have received new looms, technical assistance, and market assistance. Yet, the artisans say that policy intent has failed to reach the ground in full measure.

“The schemes are good, but what we need is a real platform — maybe an online space or a local marketplace where we can sell directly,” said Ramesh. “If we can connect to buyers, we’ll never have to sell our art at a loss again.”

As the day ended and the golden light of sunset fell across the village, the looms of Nepura kept singing their quiet rhythm. Shanti Devi was still at her loom, her hands moving with grace and purpose, weaving not just fabric but stories — stories of heritage, resilience, and hope. In her movements lay the memory of generations who have kept this art alive against all odds. These weavers are not just artisans; they are the custodians of India’s cultural identity. Each thread they spin is a symbol of endurance — proof that tradition can survive, even thrive, when held by hands that refuse to let go.

The handloom silk and cotton weavers of Nepura remind us that sustainability begins at the grassroots — in the quiet corners of villages where creativity meets courage. What they seek is not charity, but visibility and opportunity. Because if given a fair platform, the threads of Nepura will not only clothe bodies, but also keep alive the timeless story of India’s spirit.

References

- Development Commissioner (Handlooms), Ministry of Textiles, Government of India; “Bihar’s Handloom Industry: Challenges and Opportunities,” NIFT Patna report, 2023.

- Sustainability in the Handloom Traditions of India Report, Ministry of Textiles, Government of India

Surbhi Mishra is a TRIP Intern under Hamra Bihar

Mentored and edited by Sneha Yadav.