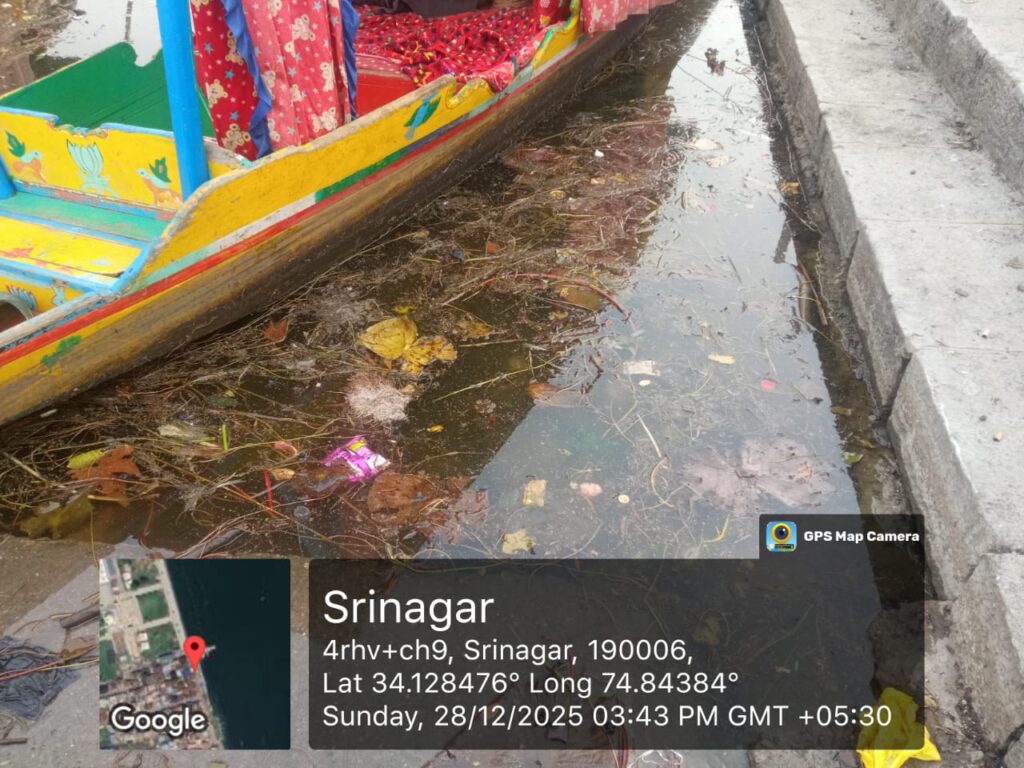

Over time, the continuous inflow of sewage has resulted in visible and persistent degradation of the Dal Lake. The water has blackened; there is foul odour and excessive weed growth across different sections of the lake.

For nearly fifteen years, Dal Lake has been silently absorbing the waste of a growing city—untreated sewage, household discharge, and institutional effluents have been flowing into its waters. While the lake continues to be projected as Kashmir’s most recognisable symbol, its quieter edges reveal a far more troubling reality: one of long-term neglect, unchecked pollution, and ecological exhaustion.

“Earlier, we could see the bottom of the lake in many places; now, the water is dark and smells of waste. This did not happen suddenly—it has been coming for years,” says Imtiyaz Ahmad Dar, a shikara operator who has worked on Dal Lake for over two decades.

Residents living along Dal Lake insist that the pollution did not appear overnight. It accumulated gradually, as wastewater inflows were allowed to continue unchecked. The untreated sewage from hostels, university-related facilities, and nearby institutional establishments has entered the lake almost daily for the last few decades.

Approximately 250 households are located along the periphery of Dal Lake. Most of these households lack proper sewerage connectivity. With no alternative disposal system, the lake becomes the easiest outlet.

“The waste from our homes has nowhere else to go,” admits a resident living near the lake. “Without drainage, everything ends up in the water.”

Moreover, institutions located close to Dal Lake contribute significantly to the pollution load. Hostel complexes and university-associated buildings generate wastewater volumes comparable to small settlements. But with inadequate and poorly maintained sewage treatment mechanisms, the pollution of the lake continues.

Over time, this continuous inflow has resulted in visible and persistent degradation of the Dal Lake. The water has blackened; there is foul odour and excessive weed growth across different sections of the lake.

Environmental specialists warn that untreated institutional effluents are particularly damaging because they contain high levels of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. These nutrients accelerate eutrophication, which ultimately leads to fish mortality.

“In some stretches, the lake no longer behaves like a lake,” observes an environmental expert. “It behaves like a stagnant drain.”

Cleaning Drives That Miss the Source

In response to visible deterioration, sanitation labourers and mechanical equipment are periodically deployed to remove weeds, silt, and floating waste from Dal Lake. De-weeding machines, dredgers, and manual cleaning teams work across selected areas, often creating a short-lived improvement.

However, locals argue that these efforts treat the symptoms, not the source. “They clean today, but tomorrow the same drains bring fresh waste,” says Imtiyaz Ahmad Dar. “Unless the sewage stops, the lake will never recover,” he further adds.

Livelihoods Under Threat

For communities dependent on Dal Lake, pollution is not an abstract environmental concern—it directly threatens survival.

Bilal Ahmed Mir, a fisherman, says fish populations have declined sharply over the years. “Earlier, we could catch enough fish in a few hours,” he explains. “Now, we spend the whole day and return with very little. The fish are disappearing because the water is poisoned.”

Fishermen have reported alterations in fish behaviour, reduced breeding, and shrinking fishing zones. Houseboat owners struggle with foul-smelling water that discourages visitors, while shikara operators face declining earnings as tourists avoid polluted stretches.

Moreover, residents living near the lake report an increase in cases of skin infections, stomach ailments, and waterborne diseases.

“We tell our children to stay away from the water,” says a local mother. “People avoid travelling near polluted areas, especially during early mornings and evenings when odour and mosquito activity are relatively high,” she further adds.

Conclusion

Without long-term ecological monitoring, cosmetic clean-up drives will continue to fail, and Dal Lake’s decline will persist. Experts stress that sewage needs to be intercepted and treated before entering the lake. The treatment plants need to function fully and consistently. Further, lake-side residents need viable community-level waste management alternatives.

Dal Lake’s future now depends on a fundamental shift—from neglect to responsibility, from surface cleaning to systemic change. If the inflow of pollution continues, the question is no longer whether Dal Lake can be saved—but how much of it will remain to be saved.

(Muskan Mushtaq is an intern under TRIP.)

(Edited and Mentored by Sneha Yadav)

About the author

Muskan Mushtaq is a passionate environmental researcher and a Zoology postgraduate from the Central University of Kashmir. She holds a strong passion for sustainability, wildlife and environmental conservation, and for combining scientific research with practical fieldwork. With this commitment, she aspires to build a purposeful career in field ecological and environmental sustainability. She is currently a TRIP Intern.

-

This author does not have any more posts.

Sneha Yadav is an electronics engineer with a postgraduate degree in political science. Her interests span contemporary social, economic, administrative, and political issues in India. She has worked with CSDS-Lokniti and has been previously associated with The Pioneer and ThePrint.

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav

-

Sneha Yadav