Higher education, for many, is an investment in hope for the future and it is incumbent upon the nation to ensure that it does not get turned into despair. Yet, higher education is generally confined to a minuscule proportion of the students mostly comprising the social and economic elites who have already accumulated enough resources. The mass of the highly educated talent pool that the country has is an invaluable resource that may be garnered as the demographic dividend, making it imperative to gainfully employ them to save ourselves from the onslaught of the demographic disaster.

A few years ago, I happened to travel with a young Norwegian for a couple of hours, who was a highly educated information technology professional running a start-up. He was curious about the rapid rise in the number of enrolments in private higher educational institutions in India. He found the phenomenon quite strange as he was unable to understand the way these institutions sustain themselves financially. As I tried to explain that they charge hefty fees to cover their operating cost and recover investments in infrastructure, he became all the more baffled. “Why would anybody pay for his/her higher education? He/She is already giving his/her time and energy and losing on opportunity cost. Why should he/she also pay for getting higher education? After all, it is the society, the industry, and the nations that too stand to benefit… would it be too much to expect from them to bear the cost of higher education of their people?”.

While I gave all the arguments that are usually advanced to support private participation in higher education – the huge gap between demand and supply, the inability of the government to invest adequate enough resources to create the needed capacity, higher private than social return on investment in higher education, private investments promote competition and efficiency, etc. He feigned to follow but I parted his company with the nagging feeling that I had failed to convince him, even partially. As I reflect on that chance encounter, I realize his difficulty in comprehending privatization of higher education even in free-market economies as he hailed from an economy that provides up to the highest level of education free of cost to its people.

Also Read: Withering Public Sector and Bourgeoning Private Sector in Higher Education

Lately, however, I have often found myself pondering about the reasons for the ever-increasing demand for higher education in the country. A web search on ‘why people pursue higher education’ throws up a sea of information as to why people must pursue higher education. These encompass a wide range of reasons comprising enabling people to pursue their passion, identify their talents, hone their skills, realize their full potential, become better human beings, better their career prospects, improve their earning opportunities, and so on.

Higher education is confined to a minuscule proportion of the students mostly comprising the social and economic elites who have already accumulated enough resources.

Higher education is confined to a minuscule proportion of the students mostly comprising the social and economic elites who have already accumulated enough economic resources to worry about livelihood and socio-economic status. They are socially and economically endowed to pursue their passion. A bulk of the students, particularly the first generation learners, however, come to higher education for economic reasons; believing it to be, probably, the most potent tool to pull themselves out of poverty and progress upon the socio-economic ladder. The present surge for demand in higher education, particularly in the developing and under-developed economies is largely attributable to the instrumentarian approach to education.

Also Read: Internationalization of Indian Higher Education

Seen in this perspective, it becomes all the more difficult to know as to why are Indians so keen on pursuing higher education at all? Sanjay Kapoor, in an article in Deccan Herald (UP Polls: Plummeting economic growth versus Hindutva, 7 January 2022), citing a noted economist Santosh Mehrotra, mentions that graduate unemployment for the general and technical higher education in Uttar Pradesh, one of the most populous provinces of the country, is currently as high as 51 and 46 percent respectively. The problem may be acute in UP but it is certainly not an exception.

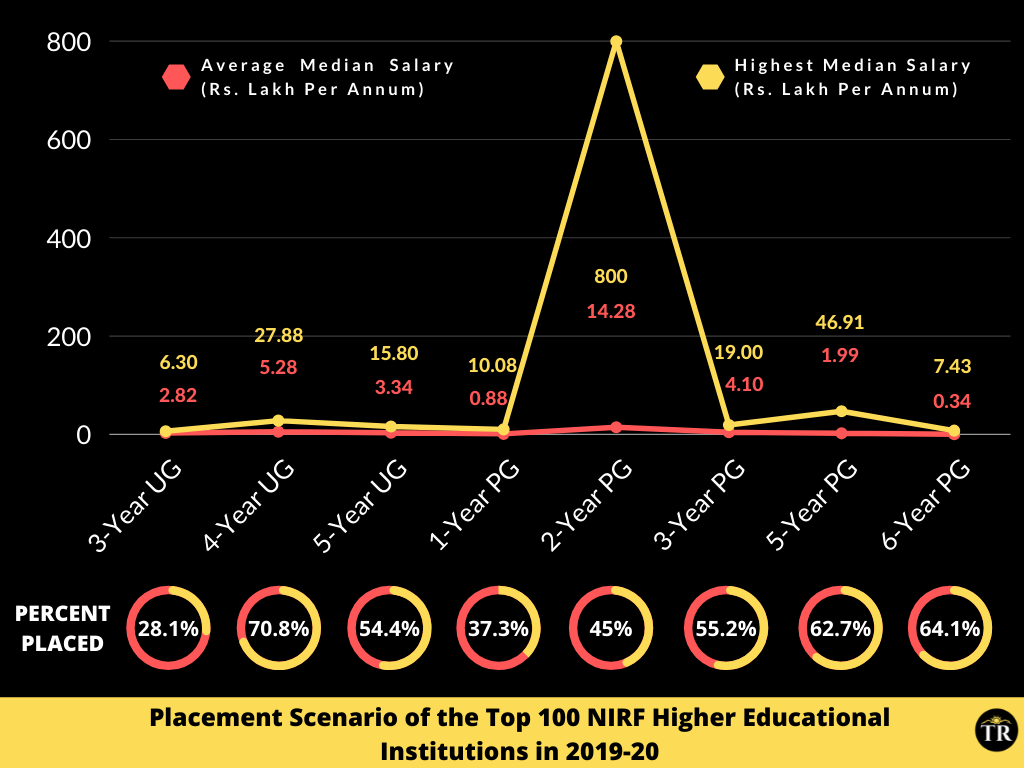

Top 100 higher educational institutions as ranked by the National Institutional Framework (NIRF) in 2019-20, report that 51.1 percent of the Under Graduate (UG) and 52.9 percent of the Post Graduates (PG) could find campus placement. It may, however, be mentioned that the placement differed significantly by the type of programmes: 3-year UG (28.1%); 4-year UG (70.8%); 5-year UG (54.4%); 1-year PG (37.3%); 2-year PG (45.1%); 3-year PG (55.2%); 5-year PG (62.7%); and 6-year PG (64.1%). If such is the case for the Top 100 NIRF higher educational institutions, one can imagine how dismal would be the situation in the rest of the 51,000 higher educational institutions in the country.

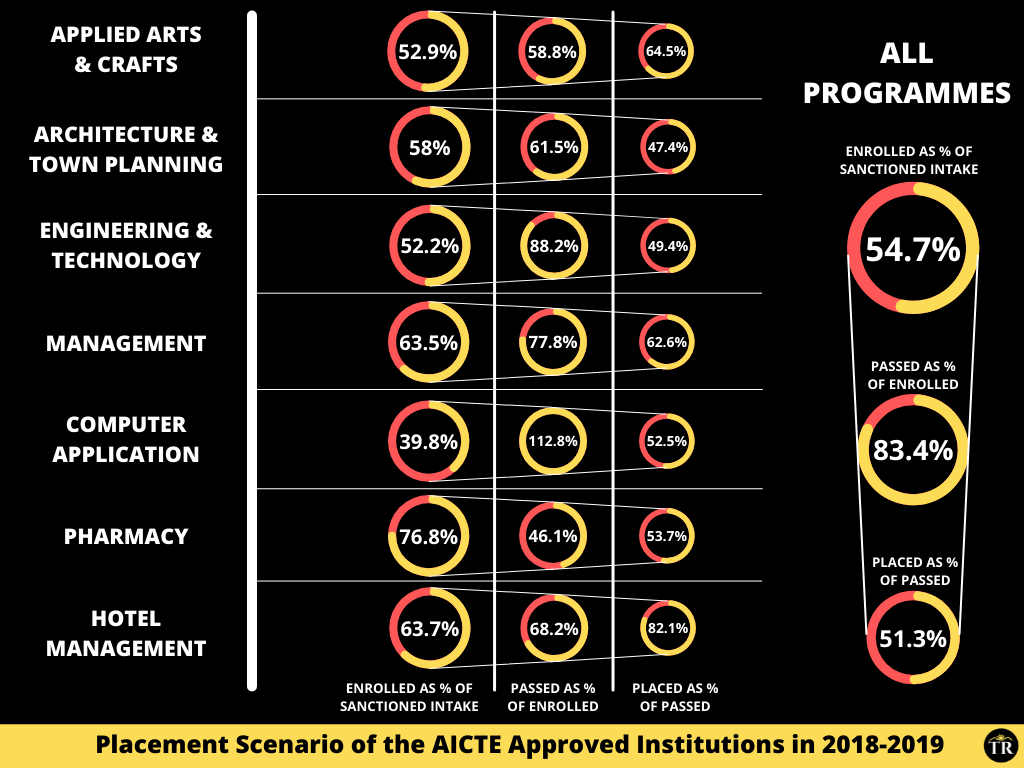

As regards AICTE approved technical programmes, data shows that no more than 51.32 percent of their graduates get placed, though the statistics vary significantly by the programmes: Applied Art (64.45%); Architecture (47.40%), Engineering & Technology (49.42%), Management (62.61%), Computer Application (52.55%), Pharmacy (53.73%), and Hotel Management (82.06%).

Many surveys undertaken by industry associations have revealed that an overwhelming proportion of the higher education graduates in India not only remain unemployed but are also unemployable. It is now a commonplace to the newspaper report that a large number of highly qualified Engineers, Bachelors’, Masters’ and even Ph.D. degree holders queue up for even menial jobs with matriculation as prescribed qualification. Such news is often cited to comment on the poor quality of higher education and to explain the reasons why higher education does not better the income and employment prospects of people with degrees.

Industry, academia, and experts may differ on the reasons for such rampant unemployment. The industry may feel that higher educational institutions produce graduates whose knowledge, skills, abilities and aptitude do not meet their requirements, thus attributing the unemployability to the poor quality of higher education graduates. Academia, on the other hand, may argue that the phenomenon is primarily due to the jobless growth that India experienced even prior to the present pandemic, while experts may explain the situation in terms of a mismatch between the demand and supply not only in terms of quality but also in terms of numbers and quantity.

Also Read: Appreciating the Importance of Teachers in Higher Education

Divergence of view about the causes of unemployability notwithstanding, none deny the prevalence and perpetuation of the phenomenon on a pan-India basis. So, why do people in India so desperately desire to receive higher education? The argument that they do so because they have nothing else to do may have been true when higher education was available nearly free of cost. This may not hold ground today when most students are compelled to study in the high-fee charging self-financed private higher educational institutions for which their parents have to pay through their nose. Why then, do people spend their time, energy, and money to get something that apparently gives them nothing except causing frustration?

Few of the graduates of Indian higher educational institutions who had difficulty in getting gainfully employed within country are regularly picked up for their talent, knowledge, skill and aptitude abroad.

There, certainly, would be some more benefits arising out of higher education, that we have not been able to fully comprehend so far. Social status, for example, could be one such reason as in India qualifications are still given some preference over income alone. Further, quite a few of the graduates of Indian higher educational institutions who had difficulty in getting gainfully employed within the country, are regularly picked up for their talent, knowledge, skill, and aptitude by employers and higher education institutions abroad. Most of them build their careers abroad with roaring success and get recognized for their distinguished career.

Also Read: Should Ph. D. be Mandatory for Assistant Professors in the University?

While most of such graduates might hail from affluent backgrounds with spare means and necessary connections, there could also be some dominant exceptions as a good number of graduates from even the deprived section of the society may be bright and brilliant enough to bag scholarship and other financial support to build their career abroad. This is, however, not to deny the fact that quite a substantial number of professionals, graduates, postgraduates, and doctoral degree holders can ill afford to go abroad. They form a good proportion of the talent pools that remains in the country hoping for a decent income opportunity and prospect for realizing their potentials within the country to support their families, sustain their motivation and maintain their sanity.

For most, however, the motivation for higher education is sustained by the expectations of better days ahead in the real sense of the word and sooner than later. Higher education, for them, is an investment in hope for the future and it is incumbent upon the nation to ensure that it does not get turned into despair. The mass of the highly educated talent pool that the country has is an invaluable resource that may be garnered as the demographic dividend, making it imperative to gainfully employ them to save ourselves from the onslaught of the demographic disaster.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are of the author solely. TheRise.co.in neither endorses nor is responsible for them.

About the author

Dr. Furqan Qamar is a former professor of management at Jamia Millia Islamia and an education advisor in the Planning Commission, now NITI Aayog, is currently the Chief Advisor to the Chancellor at Integral University, Lucknow. He has been the former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Rajasthan and Central University of Himachal Pradesh and Secretary General of Association of Indian Universities..