*This is Part One of the Two-Part Article Series on the Olympics and International Politics*

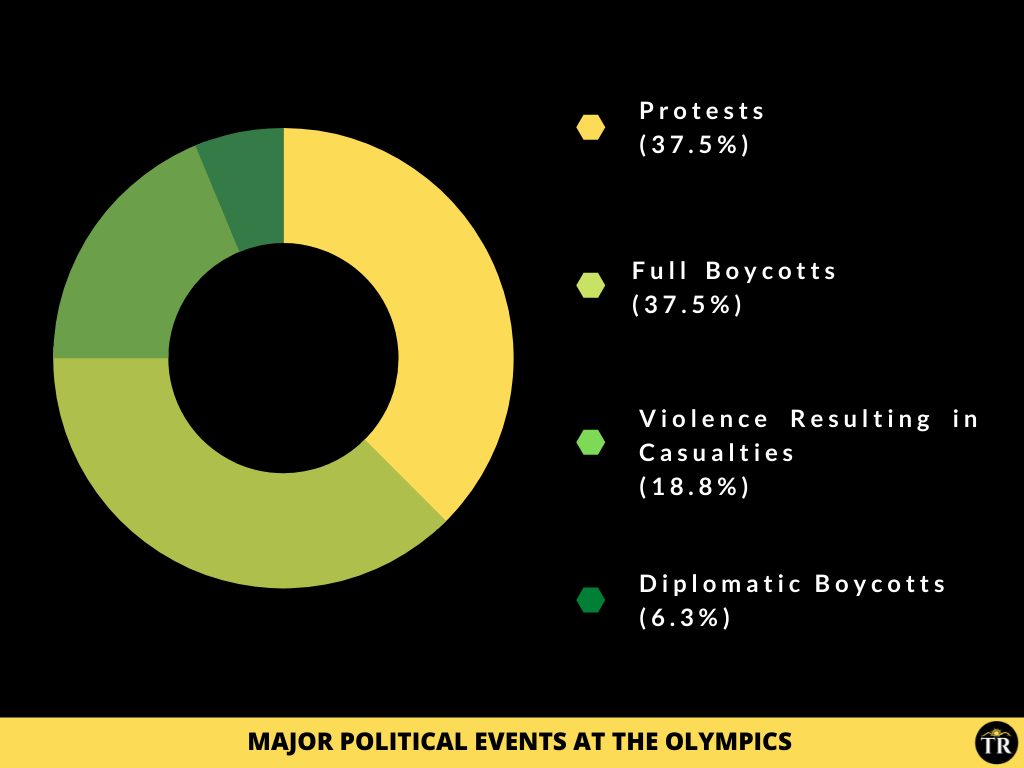

A few countries, including the United States of America, have decided to stage a diplomatic boycott of the ongoing 2022 Beijing Olympics. The Olympics and politics have had a complex relationship even in the past. Almost every Olympics has had one or multiple instances of politicisation. In Olympic history, multiple countries have boycotted the games to express dissent on the basis of international conflicts and issues. The Olympic games also have had their fair share of violence, resulting in human and infrastructural casualties over the years.

The 2022 Winter Olympics got underway this week in Beijing. Commencing in less than six months after the close of the postponed Tokyo Summer Games, there is quite a buzz surrounding the event. However, most of the talk surrounding the event is not regarding the sports, athletes, or medal expectations, but rather discussions of a political nature. A few countries, along with the United States of America, have decided to stage a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing competition. This means that even though their athletes will compete in the Games, no ministers, diplomats, or officials representing the country will make an appearance in Beijing for the entire tournament. The Chinese Foreign Ministry, the Communist Party and their embassy in Washington all responded critically to this, saying that politics should not be mixed with sports and that this decision taken by some countries was in violation of the Olympic spirit.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) spokesperson stated that they respect the boycotting countries’ decisions in line with maintaining the committee’s political neutrality while also welcoming their decision to still send athletes to the games. Multiple stakeholders and many supporters of the Olympic movement argue that the boycotting countries are politicising the games and how this could set an example for the future. However, the Olympics have always been political, ever since the first modern games were played in 1896. This is bound to happen due to the participation of countries worldwide, and the political tensions often impact the Olympics in some way. A total of 206 National Olympic Committees (NOCs) are recognised by the IOC, meaning that it has an even greater membership than the United Nations (UN) itself. Thus, the combination of factors, including the participation of so many countries, a massive audience, and a global stage, has led to the formation of complex relations between the Olympics and international politics.

Politics Inside-Outside

Being such a global body, the Olympic governing body itself faces political and legal challenges on a regular basis. For political reasons, there have also been multiple instances of countries not being invited or allowed to participate in the games. However, the key principle of the Olympic Movement has been to avoid politics from impacting the athletes and any sporting component of the games directly. For example, after Russia was found guilty of systemically violating anti-doping regulations in 2017, the Russian flag was banned from the Olympics and other sporting competitions until December 2022. Even in doing so, athletes who have not been found guilty by the country would still be allowed to freely participate in the Olympics. Therefore, the IOC and other associated sports agencies did not let the uninvolved athletes be penalised or banned for a larger violation on their country’s part. In fact, Russian contingents competed under the Olympic Athletes from Russia (OAR) and Russian Olympic Committee (ROC) acronyms and flags at the 2018 Winter Olympics and 2020 Summer Olympics respectively, going on to win a total of 88 medals combined.

Almost every Olympics has had one or multiple instances of politicisation. However, the key principle of the Olympic Movement has been to avoid politics from impacting the athletes and any sporting component of the games directly.

However, politics at the Olympics goes well beyond the legal and administrative issues, extending to multiple social issues and the larger state of international relations. In the inaugural competition held in Athens itself, France and Germany were initially unwilling and reluctant to send their athletes to the games due to their bilateral relations, even though more than twenty years had passed since the end of the Franco-Prussian War. Finally, after great efforts and attempts to convince them, both nations sent delegations to the competition. From then on, almost every Olympics has had one or multiple instances of politicisation. Therefore, there exists a strong link between politics and the Olympics, which provides an interesting and important research opportunity to be studied through the lens of international relations (IR) theory.

Protests at the Olympics

The most common form of expressing dissent is through the means of protest. The Olympics have also had a fair share of protests coming from both the athletes as well as their supporters and the general public. The very first protest at an Olympic event took place at the 1906 Games in Athens. While the IOC later withdrew its recognition of the event due to their insistence on continuing the four-year sequence of the Olympiads, the event is still remembered for a different reason. Three Irish athletes competed at the Games, but were forced to compete under British nationality because Ireland did not have its own NOC at the time and was still under British rule. Peter O’Connor, an Irish long jumper, went on to win the silver medal in his event. However, he was forced to stand on the podium under the British flag. It was then that he physically scaled the flagpole and held out the ‘Erin go Bragh‘ flag, the name of which roughly translates to “Ireland Forever.”

Following these Olympics, many athletes used the podium to express their dissatisfaction with both international and domestic social issues. A key issue, which saw multiple protests at the event, was racism. The 1936 Olympic hosting rights were awarded to Berlin in 1931. However, in 1933, the Adolf Hitler-led regime came to power in Germany. Many countries, including the US, considered boycotting the event for moral reasons, but later decided to attend the games. Hitler saw the event as an opportunity to further his master race theory of the Aryan race being superior. At the games, however, the on-field performance of one athlete dislodged this entire narrative. Jesse Owens, an African American track and field athlete, won four gold medals at the event. A remarkable photo from the long jump podium ceremony shows Owens saluting with his hand against his forehead while the silver medallist from Germany, Luz Long, and all other German officials hold the Nazi salute.

Source: CFR / AP Photo

While Owens’ performance had ruined the Nazi racial supremacy plans, Germany still came out on top of the medal table. Further, the fan support for athletes of different races and the absence of any racial discrimination at the event helped Hitler project the Nazi party as renewed and welcoming. However, back home in the US, Owens and his fellow 17 African Americans, who won a total of 14 medals in Berlin, continued to face discrimination. At the 1968 Mexico Olympics, another such act of racial discrimination was seen. Two African American sprinters, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, won the gold and bronze medals, respectively, in the 200m race. During the medal ceremony, both athletes raised their fists, wearing black gloves and the Olympic Project for Human Rights badges. Known as the Black Power salute, this was a stand against racial segregation that was going on in the US and for which both athletes faced a ban from the American and international Olympic committees. The salute was inspired by the Black Power movement that emerged in the 1960s for the rights of African-Americans and against the discrimination that they faced in the country.

Source: CNN

However, the Black Power salute is not the protest for which the 1968 edition of the event is most remembered. Ten days before the beginning of the Olympics in Mexico City, thousands of students conducted a peaceful march to protest the government’s decision to hold the Olympics in the country. They felt that the resources used for hosting the games should rather be used for funding social programmes that the country needed more of. It was also a part of the larger 1968 Mexican Movement. The event turned into a massacre after Mexican armed forces surrounded the gathering under government orders and opened fire on the crowd, leading to hundreds of deaths and more than a thousand people injured in the process. This event came to be known as the Tlatelolco massacre, and it remains the most violent and brutal memory in Olympic history.

Source: Mexico News Daily

In recent times, civilian protests against holding the Olympics have been common, especially in developing nations with demands for the immense cost required to host the Olympics to be used for welfare and development instead. The most recent protest, however, was for a different reason. In 2021, the Tokyo Olympics were filled with multiple protests outside sports venues leading up to and during the event. The city was going through an outbreak of the COVID-19 corona virus. Even when strict restrictions were enforced in Tokyo, the government was keen on conducting the Olympics as they had already been postponed once in 2020. Finally, even after large-scale rallies and criticism against going ahead with the competition, the event went through with no major disturbances.

Boycotts

While protests by athletes and civilians have a more social and domestic nature, dissent on the basis of international conflicts and issues is more often expressed by countries through boycotts. In Olympic history, multiple countries have boycotted the games by not sending a representative contingent to the event. The first such boycott was staged in 1956, at the Melbourne Olympics. For varying reasons, a total of eight countries did not participate in the games. The Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland did so to protest Russian interference in the Hungarian Revolution by invading the country. China, on the other hand, did not send athletes in opposition to Taiwan’s participation. China considered Taiwan to be a part of its own territory even though it was controlled by the Kuomintang government, which had fled the mainland in 1949 after the communist movement took power in Beijing at the end of the civil war. Lastly, Iran, Egypt, Lebanon, and Cambodia all decided to boycott the games to protest the 1956 Sinai invasion by Israel, the United Kingdom, and France.

In Olympic history, multiple countries have boycotted the games to express dissent on the basis of international conflicts and issues.

Another boycott took place at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo when all athletes who had participated in the 1963 Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) were held in Indonesia. China, Indonesia, and North Korea ended up skipping these games since they were the key countries involved in the formation of GANEFO. The next boycott came in 1976 at the Montreal Olympics. A mass boycott held by 28 African nations greatly impacted the Olympics, both economically and on the field. The reason for the boycott was to protest the IOC’s decision to allow New Zealand to compete at the event. To give a bit of context, these games were one of the many Olympics to be held during Apartheid in South Africa. The country was not allowed to participate in the Olympics right from the 1964 to the 1988 games. During this period, it was also common for many other sporting organisations as well as individual countries to not engage in any sporting events with the South African teams. However, the New Zealand rugby team toured South Africa in 1976. This enraged many African and other countries worldwide, which thus demanded that New Zealand not be allowed to participate in Montreal. However, when the IOC rejected this demand, the group of 28 African states decided to boycott the tournament completely.

The following three consecutive editions of the summer Olympics, in 1980, 1984, and 1988, respectively, saw boycotts by different countries. While the 1988 Olympics set a new record at the time in terms of the number of countries participating, a group of socialist nations, including North Korea, Ethiopia, Cuba, and Nicaragua, boycotted the games. The Olympics were held in Seoul, and North Korea wanted to be a co-host of the event. When they were not allowed to do so, they ended up boycotting the event.

You May Like: The Achilles’ Heels of China in 2022

Violence at the Games

Physical fights between athletes have been limited at the Olympics. Usually, some amount of fighting is bound to happen in any sport due to high stakes and a competitive setting. However, while such acts are against the Olympic spirit and general sportsmanship, the human harm in such cases is negligible. However, there have also been incidents when violence takes place off the field and results in bloodshed. While the 1968 Mexico incident remains the most deadly incident, another instance of violence took place within the actual duration of the Olympic games in 1972. Being held in Munich, the event is remembered as one of the darkest moments the Olympics have seen. Known as the Munich massacre, the terrorist attack took place during the games when a Palestinian group known as Black September took hostage members of the Israeli contingent. The entire incident, including the hostage-taking, negotiations, and rescue attempts, led to the deaths of multiple Israeli athletes and coaches, a German police officer, and members of the terrorist group. Another unfortunate event took place during the 1996 Olympics held in Atlanta. A domestic bombing in the city led to more than a hundred people injured and a few deaths. Therefore, the Olympic games have had their fair share of violence, resulting in human and infrastructural casualties over the years.

It is clear that however much the IOC and other proponents try to say that the Olympics are not political and should be kept separate from each other, the fact remains that the Olympics and international politics are interconnected at various levels. Both are mutually affected by each other. In the next part of this series, we will further examine the relationship between Olympics and global politics. Using concepts from IR theory, different cases of the connection between the Olympics and other topics such as foreign policy and power competition will be uncovered.

References

- Gabriel Crossley, Yew Lun Tian. 2018. China condemns U.S. diplomatic boycott of Beijing Olympics. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/china-says-us-diplomatic-boycott-winter-olympics-could-harm-co-operation-2021-12-07/.

- Vincent Ni. 2021. IOC says it ‘respects’ US boycott of Beijing Winter Olympics. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/dec/07/ioc-says-it-respects-us-boycott-of-beijing-winter-olympics#:~:text=The%20International%20Olympic%20Committee%20(IOC,Chinese%20tennis%20player%2C%20Peng%20Shuai.&text=American%20athletes%2C%20however%2C%20are%20.

- Alfred Senn. 2008. Playing Politics: Olympic Controversies Past and Present. Origins OSU.edu. https://origins.osu.edu/article/playing-politics-olympic-controversies-past-and-present?language_content_entity=en

- Politics and Protests at the Olympics. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/timeline/olympics-boycott-protest-politics-history. Accessed on February 2, 2022.

A very comprehensive and insightful article indeed. Congratulations on the publication Dhruv!

Great job Dhruv!

Congratulations on the article Dhruv! Good read.

An interesting read! Good job!

Very well written!

Pingback: Olympics and International Relations: An Intertwined Relationship

Pingback: International Relations: Beyond the Prism of 'Isms' - TheRise.co.in

Pingback: A Rundown of Sports Diplomacy - TheRise.co.in