The Jhelum’s story is both a warning and a reminder that a river can carry a civilisation only as long as the civilisation cares for it. If pollution continues unchecked, the damage will not only erase aquatic life but also erase the memory of a city built around water.

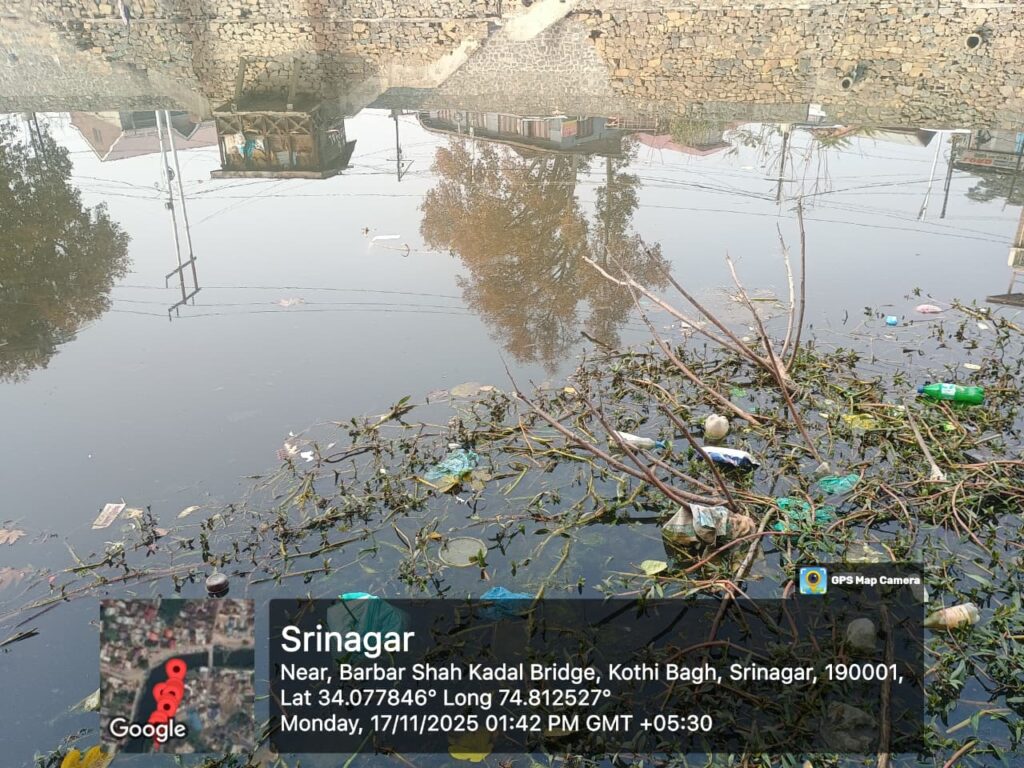

The Jhelum River, once the shimmering lifeline of Kashmir’s civilisation, now flows heavy with filth and sorrow. For centuries, it carried timber, saffron, fish, and rhythms of a city built around its bends. Today, it carries plastic bottles, untreated sewage, and the indifference of a city that grew too fast and cared too little.

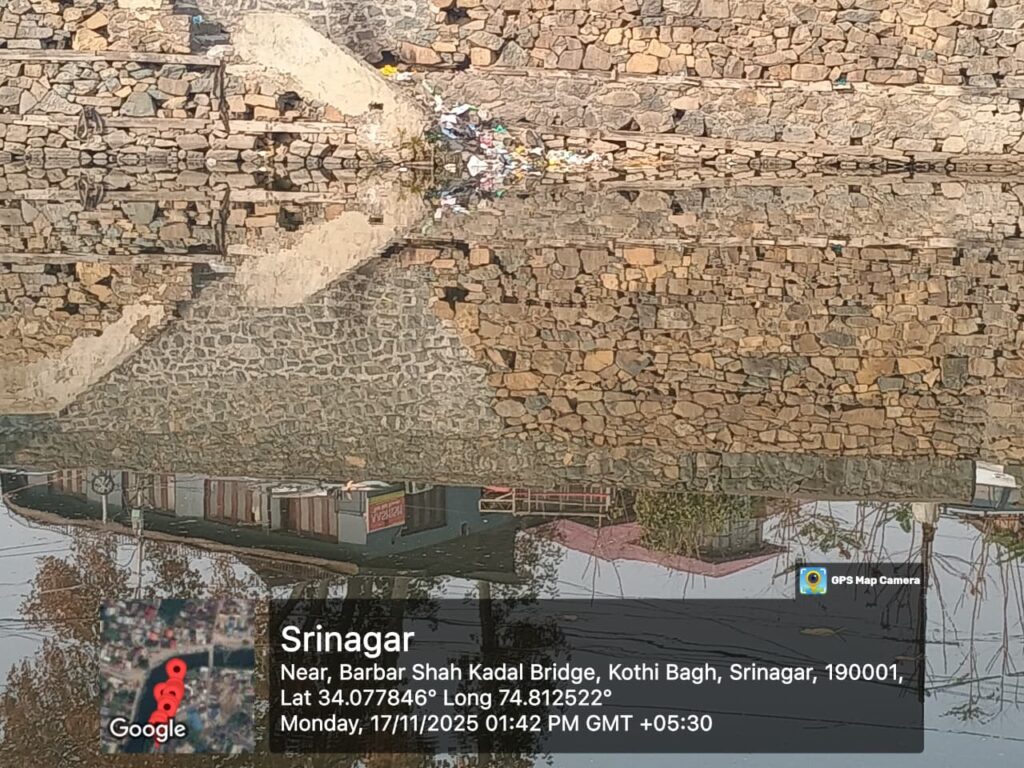

Locally known as Vyeth or Vitasta, the Jhelum River enters Srinagar after leaving the Wular Lake, winding its way through a mosaic of neighbourhoods including Nowshera, Sonwar, Rajbagh, Bemina, Lal Chowk, and the Old City (Shahar-e-Khaas) before flowing towards Baramulla and, eventually, Pakistan. Historically, this river was the spine of Srinagar’s economy and heritage, sustaining fisheries, irrigating paddy fields, and connecting a network of wetlands including Dal, Anchar, and Wular. Its ghats and riverfront settlements formed the heartbeat of the old city. Over the past few decades, however, unplanned urban expansion and unchecked waste disposal have transformed this cultural artery into a slow-moving sewer. As the river’s quality declines, the damage spills far beyond Srinagar, affecting food safety, health, and biodiversity that sustains the valley.

Scientific assessments reveal troubling changes: spikes in turbidity, inconsistent hardness, and rising microplastic contamination, especially near waste-discharge points, are clear signs of the river losing its ecological balance[9]. Water-quality reviews show a periodic decline in dissolved oxygen and high coliform concentrations downstream, driven by untreated sewage (PubMed, 2022). These degradations have altered the river’s biological character: trout and mahseer have retreated to cleaner upstream stretches, while pollution-tolerant species dominate the central basin. In some pockets of Jhelum, fish populations have collapsed entirely. Together, these indicators signal the steady deterioration of a once-thriving freshwater ecosystem.

The pressure driving this decline is varied and interconnected. The river’s pollution load majorly arises from the combined pressure of domestic sewage, agricultural runoff, and small-scale industrial discharges. Srinagar’s dense neighbourhoods, such as Habba Kadal, Rajbagh, Fateh Kadal, Bemina, Sonwar, and Nowshera, channel untreated household wastewater into the river through a maze of open drains. As per reports, over 70% of this wastewater remains untreated, carrying with it detergents, plastics, organic sludge, and nutrient-rich waste into the Jhelum[3].

Further, agricultural districts like Anantnag, Pulwama, and Budgam contribute fertiliser-laden runoff, with rainfall washing urea, DAP, MOP, and NPK into feeder streams that eventually empty into the Jhelum. A PubMed study recorded nitrogen concentrations of up to 858 µg/L and phosphorus levels near 273 µg/L in sections of the Jhelum, driven by fertiliser use and land-system changes (PubMed, 2019)[7]. These nutrient loads amplify the river’s ecological stress and accelerate water degradation.

Even without heavy industries, Srinagar’s light industrial areas add significantly to the Jhelum’s pollution. In Zainakote and Shalteng, automobile workshops and small fabrication units release untreated waste. Rajbagh and Athwajan have polishing, finishing, woodwork and textile units that also drain their wastewater into nearby channels. In the Lasjan and Pantha Chowk belt, sawmills, printing presses and packaging units contribute additional pollutants. Most of these establishments do not have effluent-treatment systems. As a result, oily and chemical-laden wastewater flows directly into municipal drains that empty into the river. According to IJIREM (2023), these unregulated discharges are becoming a significant source of chemical pollution. This growing industrial footprint adds yet another layer to the river’s already heavy pollutant burden[6].

How Pollution Hurts the River, Humans, and Wildlife

These pollutants degrade the river’s chemical, biological and physical health. Organic waste consumes dissolved oxygen, leaving aquatic life gasping for survival. Pathogenic contamination introduces harmful bacteria and viruses, posing health risks to populations that rely on groundwater adjacent to the riverbank. Physical degradation, including plastic dumps and construction debris, obstructs natural flow, forming stagnant, foul-smelling pockets that become ideal grounds for mosquito breeding. Research highlights the accumulation of heavy metals such as lead, copper, and zinc in river sediments[1]. These are pollutants that can bioaccumulate in fish and, through consumption, affect human health.

Further, triggering algal blooms that block sunlight and deplete oxygen as they decay. These events have led to repeated fish mortality incidents, undermining the livelihoods of fishermen.

Although these pollutants originate across the valley, they ultimately concentrate in the Srinagar basin, thereby causing maximum harm in the region. Ecologically, socially, and economically, the Jhelum’s decline ripples across the valley.

Yet the city’s infrastructure remains insufficient to cope with this pollution load. Srinagar’s network of sewage-treatment plants (STPs) remains inadequate. While STPs at Laam (Dalgate), Habbak, Hazratbal, and Brari Nambal function, several others remain underperforming or incomplete, allowing untreated sewage to enter the river. Bemina STP frequently overflows during rains, and the Anchar Lake STP has been repeatedly flagged for underperformance.

Environmental groups argue that meaningful revival requires a coordinated restoration plan: upgrading STPs, restoring wetlands, conducting industrial discharge audits, encouraging eco-friendly farming, and installing trash-catching barriers at bridges. Policy frameworks like the Water Act (1974) and Solid Waste Management Rules (2016) exist, but weak enforcement, illegal drain outlets, and underreported industrial waste continue to undermine progress.

For many residents, the river’s decline is deeply personal. Older Kashmiris recall a time when the Jhelum shaped childhoods and livelihoods — when fishing boats filled the river at dawn, when traders shipped goods downstream, when weddings illuminated the ghats and prayers echoed across still water. “Now we can’t even dip a hand in it,” says Mohammad Rafiq, a boatman at Habba Kadal. “The smell tells you everything.”

Yet hope persists. Community clean-ups, youth-led awareness drives, riverfront restoration under Srinagar Smart City projects, and renewed attention from experts and conservationists have begun to stir change. Advisory bodies like INTACH Kashmir, CPCB, and JKPCC have repeatedly emphasised the need for real-time monitoring, wetland revival, and stricter sewage controls. But meaningful restoration hinges on reducing waste at the source and enforcing existing rules.

The Jhelum’s story is both a warning and a reminder that a river can carry a civilisation only as long as the civilisation cares for it. If pollution continues unchecked, the damage will not only erase aquatic life but also erase the memory of a city built around water. Saving the river is not only an ecological need — it is a cultural duty.

Muskan Mushtaq is a TRIP intern.

Mentored and Edited by Sneha Yadav

References

- Anees, A., & Mir, S. A. (2022). Assessment of trace elements and heavy metals in the River Jhelum of the Kashmir Valley. International Journal of Trends in Applied Sciences (IJTAS).

- CPCB. (2023). Status of Water Quality in Major Indian Rivers. Central Pollution Control Board, Government of India.

- DownToEarth. (2023). Waste dumping is polluting the Jhelum in Kashmir with microplastics.

- INTACH Kashmir. (2022). Srinagar Riverfront Heritage Mapping and Conservation Report.

- International Journal of Environment & Health Sciences. (2021). Water quality deterioration trends in the Kashmir Valley rivers.

- IJIREM. (2023). Pollution Control of River Jhelum by Proposal of Effluent Treatment Plant.

- Khursheed, A., et al. (2019). Nutrient pollution and land-system changes in the Jhelum River. Environmental Monitoring & Assessment. PubMed ID: 26903209..

- Rising Kashmir. (2024). River Jhelum choked with waste; residents call it nature slapping back.

- Sheikh, R. M., Baskar, S., & Kuba, R. (2021). Physico-chemical analysis of Jhelum River (Kashmir). International Journal of Environment & Health Sciences, 3(3), 11–19.

I just read your post on “Jhelum River in Crisis: The Alarming Decline of Kashmir’s Lifeline” (TheRise) — and I’m so proud of you for raising your voice about this. 🙏

You’ve highlighted something incredibly important: how pollution, unchecked waste, and neglect are choking the very river that gave life to Kashmir.

Your words remind us that caring for the Jhelum isn’t just an environmental issue — it’s a cultural, social, and moral duty. Saving this river is about preserving our heritage, our health, and the future of many lives.

Thank you for using your voice. Thanks for caring. Let’s hope your post reaches many more hearts — and sparks real change. ❤️

#SaveJhelum #Kashmir #Environment #OurLifeline