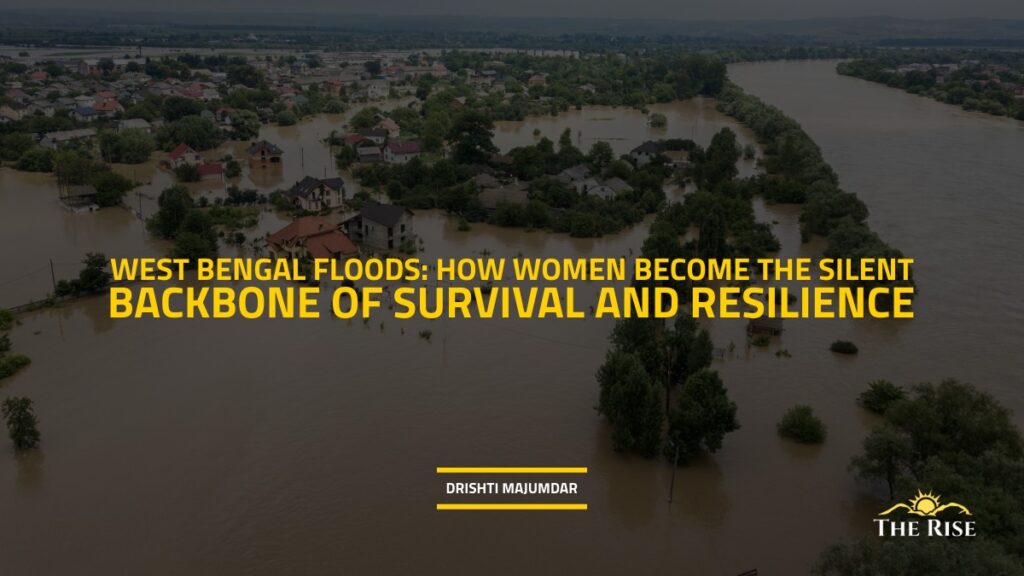

Over the years, floods in the fragile Sundarban delta have repeatedly buckled embankments, sending waters rushing in to swallow homes, fields, and livelihoods within moments. Official estimates reveal the scale of devastation amounting to more than ₹1,000 crore. The emotional toll is even more corrosive. Hours spent wading through dirty water to get food from relief camps. Nights are interrupted by the sound of rain hammering on tin roofs. For pregnant women, the lack of accessible healthcare during floods is more than an inconvenience; it’s a gamble with life.

In a small riverside village cradled by the emerald arms of the Sundarbans, dusk falls with a nervous hush as monsoon clouds gather – ominous, full, and ancient. Children’s laughter fades as mothers hurriedly pull the last clothes from the line, scanning the horizon where water meets land, memory meets dread. This is not just anticipation, but a ritual shaped by decades of monsoon floods – an annual reckoning that stitches scars deeper with each season. Here, the flood isn’t merely a natural disaster; it is a recurring chapter in the family’s epic, a shadow that both unites and tests their resilience.

Official statistics can measure the loss in numbers, yet it is in Bengali literature – woven through the verses of Rabindranath Tagore, the quiet realism of Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay, and the folk songs of the villages – that one finds the intimate pulse of survival and sorrow. In each tale, there is a familiar figure: the housewife, the mother, whose quiet fortitude becomes the axis of survival. Beyond the statistics of calamity and the chronicles of disaster-response lies her lived experience. Flood preparedness in West Bengal is not confined to policy or protocol – it is braided into everyday intuition, often embodied by the women who shape the home’s defenses.

“When the river rises, I count everything I have left, not what I have lost,” said Seema, mother of three. Her words echo the pulse of West Bengal’s flood zones, where the humble household becomes the fortress of survival, and the housewife the unsung commander.

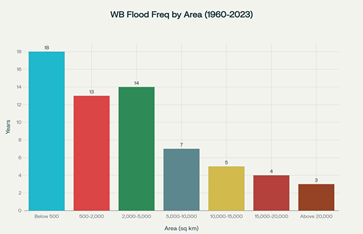

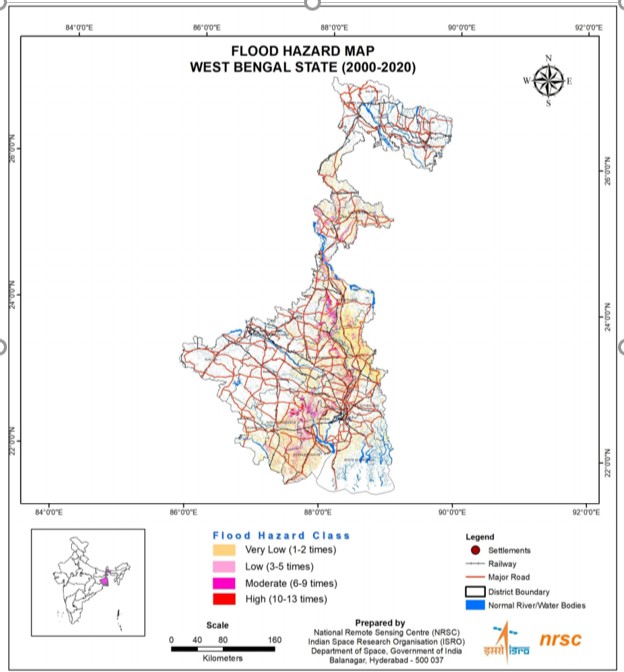

West Bengal’s location in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta blesses it with fertile lands, yet leaves it vulnerable to recurrent floods. Nearly half its territory battles water’s advance every year, and in districts like Birbhum, Cooch Behar, Hooghly, Malda, Nadia, Howrah, Kolkata, North and South 24 Parganas, Paschim Medinipur, and East Medinipur, these battles blur into daily life. West Bengal stands as one of India’s most flood-vulnerable states, with 43% of its total geographical area classified as flood-prone.

Over the years, floods in the fragile Sundarban delta have repeatedly buckled embankments, sending waters rushing in to swallow homes, fields, and livelihoods within moments. Official estimates reveal the scale of devastation: over 2.2 lakh hectares of crops drowned, 71,560 hectares of horticulture wiped out, and nearly 12,000 tonnes of shrimp lost—amounting to close to ₹1,000 crore in damages. Additionally, around 30% of fishing boats were reported to remain inoperable, further blocking a crucial income source.

Also Read: Shifting Gears: How Women Cab Drivers Are Redefining Delhi’s Urban Mobility

My land is gone. My house is gone. My husband is crippled. My sons are away. We have no crops, no firewood,” said Manuara Bibi of Baliara village in Mousuni Island in the Sundarbans. “Our lives are meaningless. We have become beggars in our own land,” she further added.

Ghatal Municipality, a low-lying patch in Paschim Medinipur, sits trapped between the Shilabati and Buriganga rivers. In 2024, Ghatal once again found itself buried under relentless floodwaters, a grim echo of a long-standing cycle. The much-talked-about “Ghatal Master Plan,” a blueprint for desilting rivers and strengthening flood defenses, has been gathering dust since 2009. Locals joke bitterly that the plan is more permanent than any embankment.

Matriarchs here are logisticians, medics, and teachers rolled into one. In waist-deep water, they learn to balance mud-stoves on bricks to cook, salvage dry rice from trunks, and carry drinking water from miles away. They have turned adaptation into an art, but it is an art forged in exhaustion.

“Every year we start from scratch,” says a resident mother of Ghatal Municipality, ferrying clean water in a plastic drum. “We can’t save enough to prepare for the next flood — the last one always takes it all.”

The emotional toll is corrosive. Hours spent wading through dirty water to get food from relief camps. Nights interrupted by the sound of rain hammering on tin roofs, each drop a reminder of the rising threat. For pregnant women, the lack of accessible healthcare during floods is more than an inconvenience; it’s a gamble with life.

Daily survival involves a series of struggles. Safe drinking water means long walks to shared tube wells, even as floods make the ground treacherous. Toilets stay submerged for months, forcing open defecation and spreading disease. Homes are cramped, flood-prone, and unsafe. Health problems pile up—waterborne illnesses, gynaecological issues, poor menstrual hygiene, and no access to care.

“Approximately 60% of patients visiting the hospital experience dermatological problems, and genital and urinary tract infections due to the usage of polluted water with higher salinity. Many women who come to the hospital for delivery are affected by genital infections, increasing the risk of infections for the unborn child,” shared Dr. Saheed Parvez, the General Duty Medical Officer at Madhabnagar Rural Hospital in Pathar Pratima block.

Adverse condition demands advanced measures. Housewives weave mats, raise poultry on raised platforms, barter honey, and tend goats. They are not merely holding the line—they are diversifying livelihoods, spreading risk like seasoned economists, even as they nurse the sick and comfort the young.

During the flood season, their role intensifies as they become vital conduits for early warning dissemination within their communities. Through informal networks like self-help groups, housewives share critical information received from official alerts or local leaders about looming floods, river levels, or emergency relief operations. This grassroots communication ensures that even those without direct access to media or smartphones receive timely warnings.

Facing some of the world’s most severe climate challenges – including rising sea levels, frequent cyclones, salinization of land, and ecological degradation. Sundarban’s women have shifted from being primarily victims of these adversities to becoming proactive agents of change.

When concrete embankments betray the people, women build living ones. In Lakshmipur, women-led efforts have transformed mangrove restoration into a vibrant, data-driven community initiative. Since 2018, the ‘Srijoni Mohila Badabon Committee’ has established nurseries nurturing over 25,000 diverse mangrove saplings. Women organize patrols against illegal logging and engage in educational outreach, ensuring community ownership sustains the project long-term.

This grassroots movement has expanded mangrove cover significantly, helping reduce erosion and safeguarding communities from floods. Their hands – once busy kneading rice dough—now press saplings into mud, building green walls stronger than any government promise.

Every time one travels through Bengal’s floodplains, the thought swirls in the mind that the stories that matter most are the ones least told. Newspapers count the hectares of crops lost, governments debate embankments, but in the narrow courtyards of submerged homes, it is a mother who quietly holds life together. In their stories, the arc bends from vulnerability to strength. They are the healers, the innovators, and unacknowledged first responders, meeting crises with a blend of ingenuity and resolve.

Drishti Majumdar is an intern under TRIP

Mentored and Edited by Sneha Yadav

References

1.“Annual Flood Report 2023 (August 2024)” Irrigation and Waterways Directorate; Government of West Bengal; https://wbiwd.gov.in/uploads/anual_flood_report/Annual-Flood-Report-2023.pdf

2.“Trial by Water: Navigating the Aftermath of Cyclone Yaas” by Somiha Chatterjee https://sprf.in/photo-archive/trial-by-water-navigating-the-aftermath-of-cyclone-yaas/

3.“Flood-Ravaged Islands of Sundarbans Need Women-Centric Interventions” https://science.thewire.in/environment/sundarbans-west-bengal-floods-women/

4.“On a small mudflat in the Indian Sundarbans, women find hope for the future” by Namrata Acharya https://earthjournalism.net/stories/on-a-small-mudflat-in-the-indian-sundarbans-women-find-hope-for-the-future

5.“Resilient livelihoods: Exploring the intersection of climate change and access to healthcare facilities for women in Sundarbans” by Susmita Paul, Pratiksha Rai https://www.cdpp.co.in/articles/resilient-livelihoods-exploring-the-intersection-of-climate-change-and-access-to-healthcare-facilities-for-women-in-sundarbans

6.“Feminist Community-led Perspectives on Disaster /Adaptations Stories from Wetland Local Women Communities in Bangladesh” by Margot Hurlbert (University of Regina), Barsha Kairy(University of Regina), Ranjan Datta (Mount Royal University). https://atlantisjournal.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/view/5802

7.“Gender and Disaster Resilience” by Sandra Bhatasara. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-4577-0_7#citeas