Apart from the poor economic condition, their social mobility is also an issue. Waste picking carries heavy caste and class stigma. Many waste pickers belong to marginalized communities and face daily verbal abuse. Their children are bullied in schools, reinforcing exclusion and a sense of inferiority.

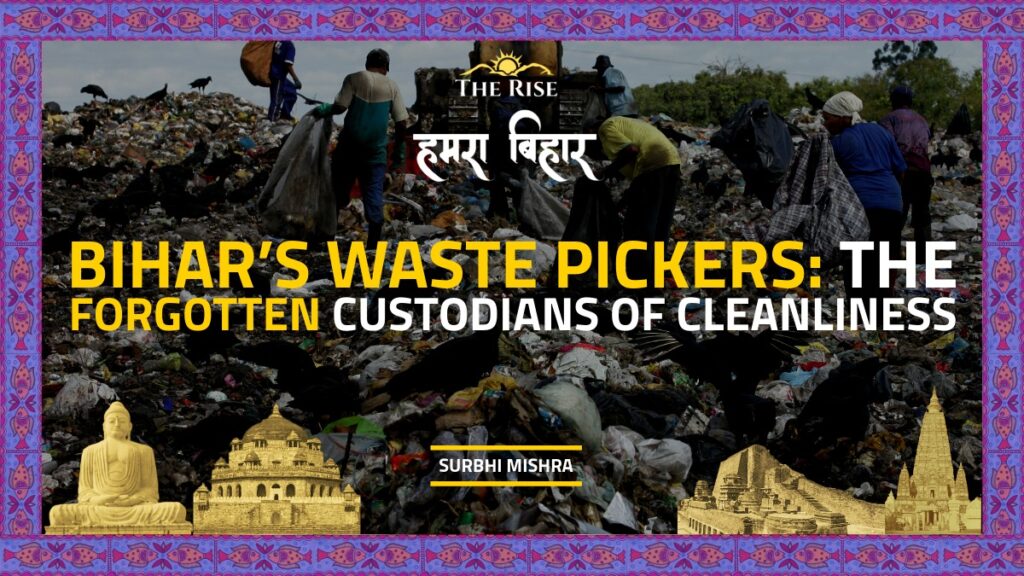

In the Ramchak Bairiya dumping yard on the outskirts of Patna, 32-year-old Seema Kumari sits through a landscape of rot and ruin to stitch together a day’s meal for her children. Wearing torn slippers and an old dupatta over her face, she moves through heaps of rotting garbage, fishing out plastic bottles and rusted metal.

“When I’m lucky,” she says, “I make ₹150-200 a day; on other days, the family sleeps hungry.” As the city sleeps, Seema and hundreds like her stay awake in its garbage, finding life in what others throw away.

It is the story of not just Seema, but of thousands of waste pickers across Bihar. These women, men, and children keep the cities breathing, quietly holding up the state’s waste economy, yet remain unseen, uncounted, and unprotected by the system they silently serve. Bihar generates nearly 26,000 tonnes of waste daily, but the very people managing it struggle for even the most necessary necessities of life- like food, clean water, and sanitation facilities, and legal identity, trapped between survival and invisibility. To understand their life better, TheRise talked to the waste pickers of the city of Nalanda, Gaya, and Muzaffarpur.

The waste is rarely segregated at source. Plastic, paper, and metal are mixed with food waste, biomedical waste, and other hazardous materials. Into this tangle step the waste pickers: with sacks, handcarts, or bicycles, they comb through the public bins, streets, and open dumps, separating anything of resale value.

Once collected, the waste is sold to middlemen or scrap dealers, who in turn sell it to large recycling units. Without bargaining power, these pickers are often forced to accept whatever price the buyer offers. On average, they earn ₹100–₹250 a day, an income that is barely enough for food and rent.

“Sometimes, I earn ₹180. If it rains, I earn nothing. The scrap dealer decides the price—what can we do?” said Ramesh Yadav, a 42-year-old waste picker in Gaya, expressing his vulnerability. Middlemen buy recyclables at exploitative rates, keeping families in debt. With no access to savings, banking, or credit, most of these waste pickers live hand-to-mouth.

Municipal vans sometimes collect mixed waste, but recyclable recovery still depends on thousands of informal workers. The remaining mixed waste is dumped in open yards or landfills, adding to the pollution levels and posing serious health risks.

Also Read: How Bihar Is Turning Sports Into a Tourism Powerhouse

Waste pickers handle hazardous mixed garbage—including biomedical waste, sharp metal, and hazardous chemicals—without basic protection like gloves, boots, or masks.

“I’ve been cut by glass many times. Sometimes I get a fever or rashes, but I can’t stop working. If I don’t go, we don’t eat,” says Seema, showing scars on her hands. She further pointed out that, like her, many waste pickers suffer from chronic cough, asthma, and skin infections caused by constant exposure to toxic smoke from burning waste.

Most waste pickers live in makeshift settlements near dumpsites, without clean water, electricity, or toilets. Some rely on tanker water or nearby drains for washing. Living beside garbage heaps exposes families to constant foul odour and mosquito-borne diseases.

Healthcare remains mostly out of reach of these waste pickers. Most are excluded from state health schemes and cannot afford private clinics. A 2024 national study found that nearly half of informal waste workers suffer injuries annually, yet only a few seek treatment due to high out-of-pocket expenditures.

Climate change and frequent floods in north Bihar further worsen the condition of these workers. During monsoon floods, their huts are often washed away. “When it rains, garbage floats away, and so does our income,” says Meera, a waste picker based in Nalanda.

Apart from the poor economic condition, their social mobility is also an issue. Waste picking carries heavy caste and class stigma. Many waste pickers belong to marginalized communities and face daily verbal abuse. Their children are bullied in schools, reinforcing exclusion and a sense of inferiority.

“Teachers used to call me ‘kachre wali’,” says fourteen-year-old Pooja, who helps her mother pick waste in Nalanda. The humiliation often becomes unbearable, eventually pushing these children to drop out of school. Children like Pooja often join their parents at dumpsites from a young age. This early exposure not only robs them of education but also traps them in a cycle of poverty and exclusion. This social isolation strips them of dignity and identity, despite their vital contribution to public health and environmental sustainability.

A large proportion of Bihar’s waste pickers are women, who shoulder both domestic duties and waste picking responsibilities. Shanti Devi, a 35-year-old waste picker from Muzaffarpur, leaves home at 5 a.m. and returns at dusk. “I walk 10 kilometres every day, earn ₹120.” Like children, these women also face sexual harassment, verbal abuse, and unequal pay. They are rarely included in decision-making, neither at home nor within municipal waste systems.

Instead of recognition, these waste pickers often face police harassment. Their collected materials are confiscated, or they are fined for “encroachment.” Evictions from dumpsites are common, especially when private contractors take over municipal waste zones.

While Bihar is planning integrated waste management projects and material recovery facilities, informal workers are often excluded from these developments, leaving them displaced rather than integrated. Although many individuals possess Aadhaar or voter IDs, they often lack proof of residence and employment documentation, which prevents them from accessing schemes such as Ayushman Bharat health insurance, ration cards, or housing programs. Without official recognition, they risk eviction or replacement by private contractors

Although the Solid Waste Management Rules (2016) emphasize segregation and recycling, implementation often excludes informal workers. Bihar’s new Integrated Solid Waste Management Project (Patna Cluster)—aimed at processing 1,600 tonnes of waste per day—has no formal plan to integrate existing waste pickers.

To address the long-standing neglect of informal waste workers, the government launched the NAMASTE Scheme in 2023. The initiative aims to formally recognize waste pickers by providing them with occupational ID cards and linking them to social security and insurance benefits. However, in Bihar, awareness and enrollment under the scheme remain extremely low, leaving most waste pickers outside its reach.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Waste pickers in Bihar form the invisible backbone of urban waste management. They perform the work which municipalities fail to manage—recovering and recycling tonnes of materials daily—yet they remain unrecognized, exploited, and unprotected.

To create an inclusive and humane waste system, Bihar must legally recognize waste pickers and integrate them into municipal systems. Mandatory provision of safety gear, periodic health camps, and insurance coverage is essential to ensure dignity of work and safety at the workplace. Access to the social security scheme must be expanded to include both men and women waste pickers. Further, technology should be leveraged to promote waste reuse and recycling, paving pathways for the upward mobility of waste pickers.

By acknowledging their contribution and restoring dignity to their labour, Bihar can build a cleaner, more inclusive, and sustainable future—one where the people who clean our cities no longer live in their shadows, but stand recognized as true custodians of urban cleanliness.

Surbhi Mishra is a TRIP intern under Hamra Bihar.

Mentored and Edited by Sneha Yadav.