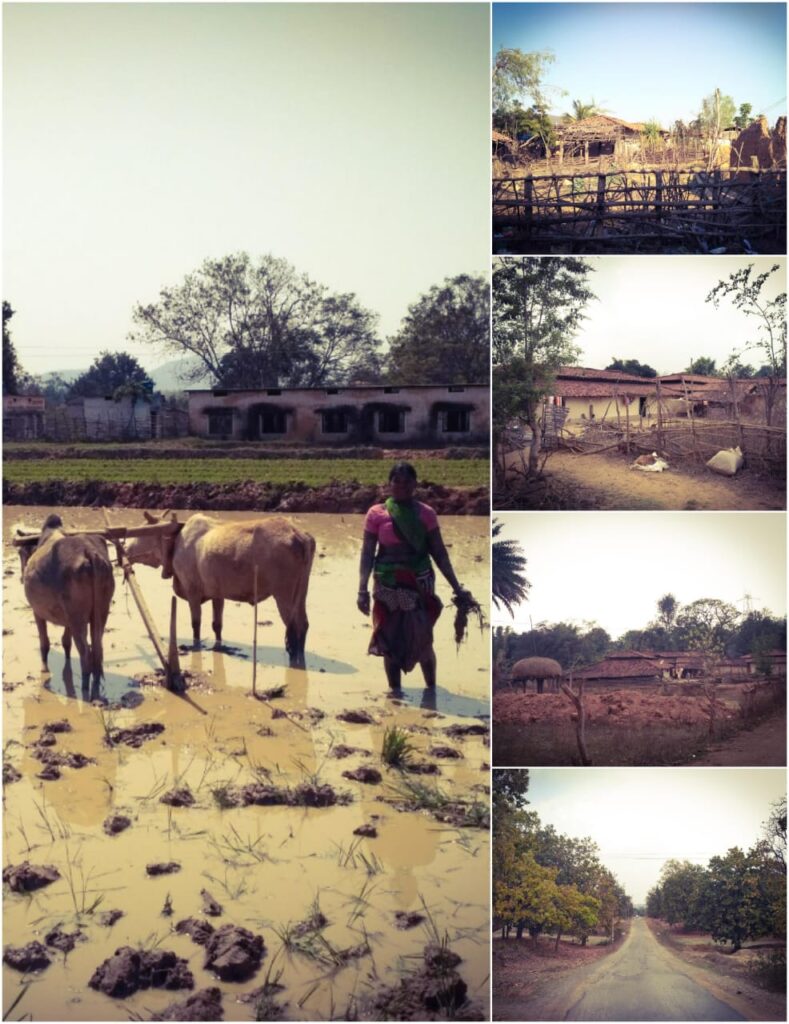

Exploring social and administrative challenges from the grassroots lens to understand its repercussions on the dropout of scheduled tribe children across government schools in Dharamjaigarh block of Raigarh district in Chhattisgarh.

The 2011 Census Report of India estimated a surge of almost 254 million youth population between the years of 1971 to 2011. It was further estimated that by 2020, the average age of an Indian would be 29 years, compared to 37 and 48 for China and Japan respectively. The European countries are also facing an ever ageing population crisis because of low fertility and mortality rate. However, for a country like India where the youth account for more than half its population, it is indispensable to have a quality education system in place for realizing the vision of a vibrant and prosperous nation.

The Government of India has already mandated that education must be free and compulsory during the elementary stages of schooling. To increase student enrolments and curtail dropouts, various provisions like the mid-day meal, free stationeries, free uniforms, free workbooks, and scholarship schemes have been made available. Although statistics point at a near 100 % enrolment for the primary age group, the number of school-going children from classes I to V amounts to only 71.86 % whereas, by the end of elementary education, there remains only 50.8 % of children enrolled in the public school (Planning Commission 2011).

When the government has taken numerous measures to universalize elementary education, why are dropout rates still so rampant especially in rural India? Are the government-sponsored education schemes reaching children in marginalized communities? Or is it the cultural practices that are inhibiting children from continuing their schooling?

Also Read: Students Steering the Education Wheel through Stormy Virus

Background

The purpose of this study is to understand drop out in elementary education and high school across various scheduled tribe communities in the Dharamjaigarh block of Raigarh district in Chhattisgarh with a focus on scheduled tribe (ST) communities in Chhattisgarh; because children of marginalized communities are at a greater risk of dropping out of school especially in rural areas and this state in particular because of its large number of ST population and poor literacy rate.

Definition of Dropout

For this particular study, a drop-out has been defined as a child who leaves school before completion of a terminal point at a given level of education, or in certain cases, remains absent from school for more than 45 days continuously without duly informing the school authorities. It is to be noted that the first part highlights the conventional definition of a dropout as suggested by NCERT, whereas the second part has been propounded after having looked through relevant literature reviews to take into consideration the discrepancies between drop-outs and non-school going children.

The Right to Education Act makes it compulsory for children between 6 to 14 years of age to attend school. It is the responsibility of the local authority to ensure admission, attendance, and completion of elementary education by all children in this age group. The local authority in the context of the study refers to school teachers who are tasked to make sure no child is deprived of education in the community, as well as comply with the regular responsibility of teaching in the school.

You May Like: Calibrate Crappy Education in COVID Aftermath

The above definition, thus, agrees that a child who remains absent from school for many months together without duly informing the school authorities is considered a dropout. However, in the context of the research study, such children are not marked as dropout but as absent in the school register. On one hand, there are parents who are unwilling to send children to school due to poor socio-economic conditions in the family, and that repeated perusal by the teachers under such circumstances turns out to be completely futile, while, hampering the instruction time of other children in school. On the other hand, failure to act in accordance with the RTE Act will bring upon much criticism from the higher education authorities for not doing enough to enroll children from the community into public schools.

This explanation helps us understand why teachers have no other alternative than to mark children who do not attend school for months together as absent and, instead, focus on providing education to the larger number of pupils who turn up to school everyday. If the research study had been approached only by considering the definition provided by NCERT, no dropouts would have been found for the elementary years in the region.

Data Collection & Sampling

During the research study, 2 government primary and high schools were visited to collect data on dropout children.

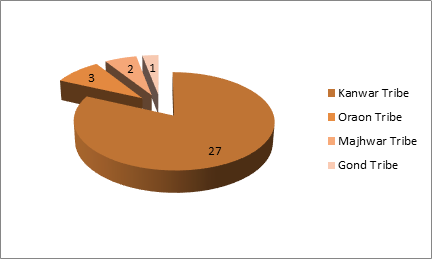

The list included a total of 33 children belonging from the scheduled tribe communities of Kanwar, Oraon, Gond & Majhwar. Random sampling was used to identify 6 children for conducting semi-structured interviews in presence of the parents at their host communities. Informal discussion with school teachers and members of the larger community was undertaken to account for their perception on children’s dropout in the region. A mix of both qualitative and quantitative approaches was used all throughout the research study.

Also Read: Time to Rethink and Reform the Examination System

Quantitative Research Findings

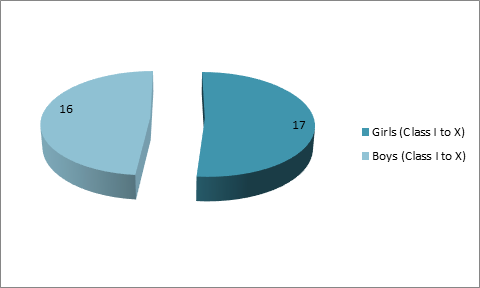

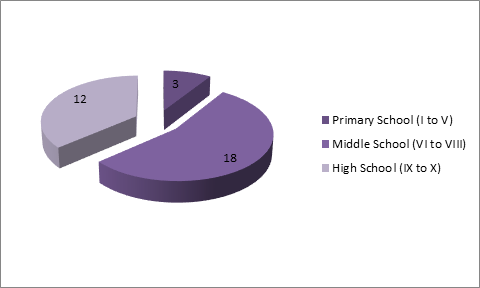

The quantitative study which was carried out across four government schools indicates a total of 33 children have dropped out. The analysis further highlights the distribution of dropouts under the following variables of tribe, gender and grade.

TRIBE: The four schools which were visited during the study are located in communities that are primarily inhabited by a large number of Kanwar tribes. Perhaps, that could be the reason why the data suggests a greater number of dropouts for this particular tribe. The common occupations which are taken up by scheduled tribes in the region involve livelihood activities such as farming, working as wage labourers in construction sites and open coal mines, domestic work, selling Tendu leaves and wine made from Mahua flowers in the local market.

GENDER: The finding suggests that dropouts for boys and girls are almost similar in the region because there is a vital need even for the younger members, irrespective of their gender, to contribute in sustaining the family. In most cases, it is the elder sibling who drops out of school to help at home. Boys generally help the father in the fields or at construction sites, whereas girls take care of the household chores right from fetching water & wood to cooking & taking care of younger siblings, while parents are away at work. However, at the time of harvest season, both boys and girls go to the forest to collect Tendu leaves (used in making local cigarettes) and Mahua flowers (used in making local alcohol) and often miss out on going to school because by selling each of them, the family can make a profit of up to ₹50 per kilogram.

GRADE: The data presents high dropouts for middle and high school because children of the primary age group are still too small to support the family economically. However, there are some dropouts even in the primary age group owing to extreme poverty in the family. The general outlook of parents is to send children to school at least till the completion of elementary education because of government-sponsored freebies. When children go to school, two basic economic necessities are taken care of: food and clothing. The former benefit implies that parents have fewer stomachs to feed during the day since children are provided with the mid-day meal, whereas, the latter allows children to have a decent pair of uniform among other worn-out clothes which they generally are seen wearing even during the non-school hours. However, it is rather alarming to have more dropouts during the middle school stage than high school because after the elementary stage, children are no longer provided with mid-day meals nor is it the teachers’ responsibility to follow up with children in case they remain indefinitely absent.

Moreover, prolonged absenteeism without duly informing the school authorities will only lead to the child being marked as a dropout. Likewise, for those children who have absented themselves in the elementary classes for months together and happen to turn up for the board exams, it is very likely that they would fail in the examinations for they would not have acquired the necessary grade-level competence. These arguments only point to the conclusion that the number of dropouts for high school ought to be greater than the transitioning period from primary to middle school, however, the data above highlights otherwise!

Also Read: When Schools look like the ‘Garden of Selfish Giant’!

The reason why there is a higher dropout during this transitioning phase is that the primary and middle schools are mostly not within the same campus. The completion of primary classes marks the end of a school stage and given the socio-economic condition of families in the region, some prefer taking out their children from school because they are physically more capable to support the family financially. Hence, children as young as twelve years, accompany their parents to the fields or construction sites to assist with labor work.

These children, who unofficially drop out after the primary stage, however, have their names registered in the nearest government middle school in the locality by virtue of primary school teachers as it’s mandatory to provide free and compulsory education to children in the age group of 6 to 14 years. Although officially enrolled, they never turn up to school. ‘Ghost students’ is the more popular term that has been coined to refer to these absent students who have been marked as enrolled in the school register but fail to attend classes.

Also, considering the definition of a dropout that has been formulated for this particular research study, we see why the data presents higher dropout for middle schools than high schools. The government statistics on the contrary would consider ‘ghost students’ as enrolled in schools given the government’s commitment to realize universalization of elementary education.

You May Like: Technological Transformation in Higher Education: Myths and Realities

Qualitative Research Findings

Perceptions of Dropout Boys

While interacting with four dropout boys, it was sensed that they were all eager to continue their schooling but given the extreme poverty in the family, and in some cases being the eldest sibling, there was a dire need to contribute towards the family’s sustenance. The parents informed that despite sending their child to school, no proper employment in the locality was achievable. Instead, preparing the child right from an early age to follow the same family occupation could make him a more responsible adult. Moreover, in a multi-grade classroom of over 40 children, there is very little learning happening, as a result, children do not have the necessary grade-level competence. By the time they transition to secondary school, the system will have officially declared them as incompetent so dropping out of the education system by the elementary stage will not only provide early financial support but also save the family’s dignity.

During the survey, it was noticed that the dropout boys had similar education levels as their fathers while in some cases, perhaps, a class or two more. The boys generally work at construction sites and open coal mines as contractual daily wage labourers. Although circumstances have pushed them to get involved in child labour, all four boys’ had noble aspirations to serve society. Three of the boys aspired to become teachers, while one dreamt of serving in the police force!

Also Read: Educational Supremacy in ‘Vishwaguru’ India: A Long Way to Go

Perceptions of Dropout Girls

Interviewing the dropout girls showed that after completion of elementary education, the parents discouraged them to study further as there was no high school in the same village. The government on the contrary has made provisions to offer a marriage settlement amount of approximately ₹50 thousand worth of essential amenities, as well as bear the entire cost of arranging the group wedding ceremony provided girls from the backward tribes complete their higher secondary studies. In addition to the distribution of cycles to girls upon enrolling in class IX, the Saamuhik Vivaah is another way to motivate parents to send girls to school until they complete their higher secondary education.

The interviewee girls who discontinued schooling after elementary education belonged to one of the most backward tribes in the region known as Pahari Korwa. One of the girls informed that she was already pregnant because the cultural norm in the community promotes child marriage. The customary practice encourages both girls and boys to live in an open relationship with due consent from their parents. Once the girl gives birth to a healthy child, she is then given for marriage. In case of a miscarriage or the child is born with any kind of deformities, the relationship comes at once to an end. In such patriarchal communities, girl children are given for marriage as early as after completion of elementary schooling because feeding another mouth is considered as an additional financial burden on the family. Both the girls had no aspiration because from the beginning they were aware of the marriage custom and that after completion of elementary education, they will have to discontinue schooling.

Challenges to Schooling in the Local Context

While talking to community members, it was learnt that the transfer of caste certificate remains a big hassle when it comes to enrolling children in the middle or high school in the neighbouring villages. Many villages do not have the provision of upper primary and secondary classes; as a result, the child needs to be admitted to another school which is often located at a distance of more than 5 km.

During primary education, the caste certificate issued by the village Sarpanch is sufficient; however, when the child needs to be enrolled in a different school that falls under the jurisdiction of another ward, it becomes essential for parents to provide a transfer certificate which is authorized by the Tehsildar’s office. This entire process is cumbersome and time-taking. which necessarily results in loss of family wages for several days. Moreover, some parents find children physically more capable to help in livelihood activities by the end of class 5, so they are reluctant to invest time in acquiring the necessary paperwork to ensure the continuity of their child’s education.

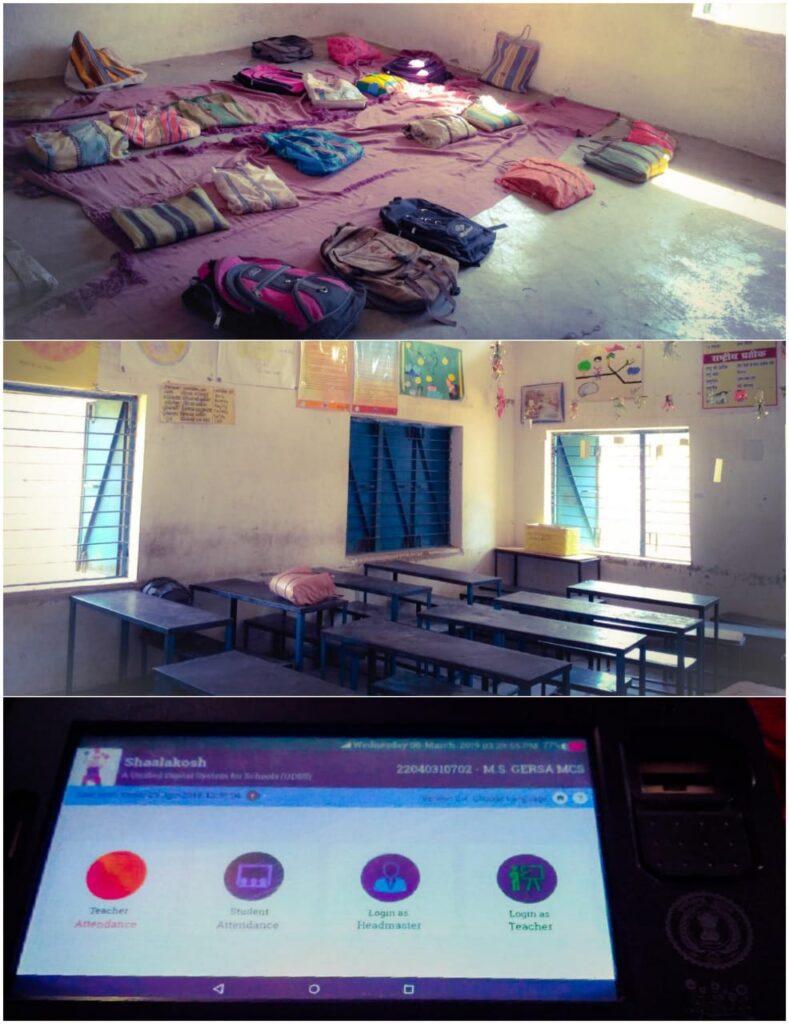

The parent’s community finds the school curriculum to be aloof from the everyday lived experiences of children as one of the root causes leading to boredom and subsequent school absenteeism and dropouts. Moreover, high pupil-teacher ratio, multi-grade classrooms and dearth of teachers in government schools also lead to poor grade-level competency in children.

Teachers’ Perspective on Challenges to Schooling

The informal discussion with teachers showed that despite several villages having a middle school in the same community but in a different campus, some parents prefer not to enroll their child in the subsequent schooling stage because physically they are more capable of supporting the family to make a living. The Right to Education Act mandates that it is the responsibility of the local authority to ensure free and compulsory education of children in the elementary years. However, when children drop out in the transitioning stages of schooling, it becomes very challenging for teachers of the following grade to track students only by the details given in the register with no first hand contact.

You May Like: Loosing sheen of Guru Devo Bhava: An Introspection

The teachers find that there is a lack of encouragement and awareness from the parents’ community towards sending children to school. In large families, the older siblings generally drop out in the early stages of education to help parents sustain the family. The livelihood activities require a lot of physical exhaustion throughout the day; as a result, there is excessive consumption of local liquor.

Drinking oftentimes leads to domestic violence in the family, thereby, inflicting psychological and emotional harm in children’s development. Teachers believe its ramification influences children to lose interest in education, arrive late or even remain absent from school for a prolonged period of time.

The teaching staff has also pointed out that the recruitment of teachers has long been pending to fill the existing vacancies across government schools in the region; as a result, they have to fulfill all the administrative formalities as well as merge classes to ensure education is being provided to all children. For instance, on a given day, teachers need to update the attendance of children onto their phones, school tablet and register during the morning hours and after the mid-day meal program.

The teachers felt that if they were given respite from administrative responsibilities and the schools were equipped with necessary teaching-learning materials as well as human resources for looking into the management processes and providing subject-specific instruction, the objections raised by parents around multi-grade classrooms, high pupil-teacher ratio and poor student learning outcomes can certainly be addressed.

Also Read: 2020: A Year of Shambolic Education Burdening Learners

Limitations of the Study

– The interviews were largely restricted to the Kanwar tribes who lived in the nearby villages of Dharamjaigarh block as these could be easily accessed using the public conveyance as compared to the interior parts of the forest where the more marginalized tribes of Oraon, Gond and Majhwar live.

– The interaction with the Kanwar tribe happened mainly in Hindi and a mix of Bangla and Odia. However, for understanding the world views and lived realities of the more marginalized tribes, the help of a translator had to be taken as the communication happened in the local dialect.

– The village visits were undertaken mainly in the morning and afternoon time. Hence, it was not always easy to find dropouts in the communities as most of them were away from home busy in some livelihood activities.

Conclusion

The research study points at a host of social and administrative issues causing children to drop out of schools. I believe the first step to address such a problem is to first acknowledge its existence and second a strong determination to find alternatives to solve the issue which is at stake. Given the state of affairs in schools in the region, I think a systemic level intervention can indeed help address the issues concerning caste transfer certificate, enrolment of ghost children, maintenance of multiple attendance records and overburdening teachers with admin tasks. Similar to the cycle distribution scheme, Saamuhik Vivaah and various other student-centric scholarships, the local governing body will need to organize awareness campaigns to educate parents on the importance of education as well as boost rural employment. I believe education holds the key to not only challenge gender-biased practices which are still religiously followed in the communities but also to break free from social stratification and to rise in social mobility.

References

- Planning Commission. (2011). Report of the expert group to review the methodology for estimation of poverty (No. id: 4531).

- Chandramouli, C., & General, R. (2011). Census of India 2011. Provisional Population Totals. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Nuepa (2014) Education for all towards quality with equity India. – Government of India, Ministry of Human Resource and Development.

- Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act. (2009)

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are of the author solely. TheRise.co.in neither endorses nor is responsible for them.

About the author

Utsarga Mondal has completed his M.A. in Education from Azim Premji University. He is currently serving as an AIF Clinton Fellow with the American India Foundation.

Pingback: Quality Education: A Luxury or A Fundamental Right? - TheRise.co.in

Pingback: Regulations Impede Excellence in Higher Education - TheRise.co.in