When language is valued, it becomes a force for unity, but when imposed, it creates division. India’s unity will be strengthened not by uniformity, but by embracing and celebrating its rich diversity.

In 1961, the Barak Valley Language Movement pointed out how hard it is for unity to grow when a diverse democracy tries to force everyone to speak the same language. This situation arose when the Assam government attempted to make Assamese the sole official language, overlooking the concerns of other linguistic communities, particularly the Bengali-speaking population of the Barak Valley.

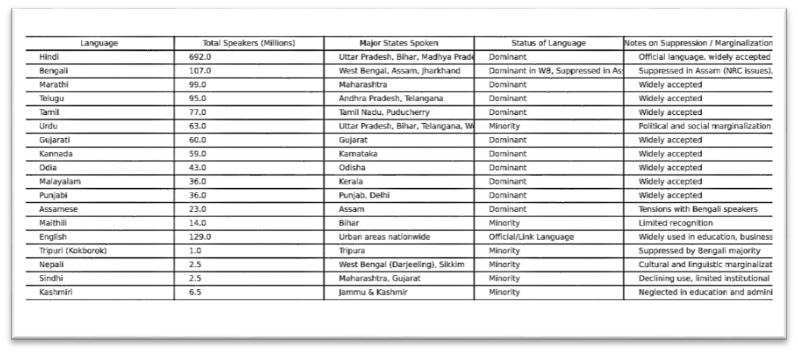

Besides being a way to speak with others, language clarifies who we are culturally. India’s diversity has significantly influenced its nation-building process, particularly through linguistic accommodation. To address this, the Eighth Schedule was introduced, and states were reorganized along linguistic lines in 1956. However, the concept of linguistic federalism has not always led to considerate or inclusive decisions by public officials.

Also Read: India’s Grand Strategy: Economic Reforms, Global South Diplomacy, and Regional Integration

It was in the early 1960s that the Barak Valley Language Movement happened, in response to Assamese being declared the single official language in the state of Assam. Many Barak Valley residents, who spoke Bengali, saw this move as a threat to their cultural identity. Failure by the state to involve groups with different beliefs resulted in the outbreak of one of the saddest events in India after independence.

Historiopolitical Context

Ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity was very strong after Assam gained independence. The Barak Valley’s majoritarian population, consisting of Cachar, Karimganj, and Hailakandi, was Bengali-speaking, while Assamese was common in the Brahmaputra Valley. In April 1960, the Assam Pradesh Congress Committee suggested making Assamese the only official language in the state. Chief Minister Bimala Prasad Chaliha presented the Assam Official Language Bill in the Legislative Assembly on October 10, 1960, and it was passed on October 24, 1960. Because of this act, Assam’s other languages went unnoticed, and little was done to help linguistic minorities.

The Rise and Tragic End of the Movement

On May 19, 1961, a peaceful satyagraha at Silchar railway station turned tragic when paramilitary forces opened fire on demonstrators advocating for the official recognition of the Bengali language. The movement was cut short as eleven people died, including young people and regular employees, in one of the bloodiest states’ responses to a peaceful language campaign.

Kamala Bhattacharjee was one of those martyred. Aware of its significance for a truly inclusive democracy, she participated with conviction. She was shot dead by the police, becoming the first female language martyr in India. The meaning of her sacrifice holds deep meaning, not only highlighting the role of women in the postcolonial political scene, but also symbolizing the emotional and cultural value that residents of Barak Valley share with their mother language.

Almost 40 years since their deaths, these 11 heroes are still not recognised as Shaheeds by the Assam Government. This lack of recognition has fostered a sense of resentment among the people of Barak Valley, especially as other regional heroes across Assam and beyond are acknowledged in government records, their families receive pensions, and their sacrifices are honoured on official occasions. Although May 19, every year in Barak Valley, is observed as Bhasha Shahid Divas, marked by candlelight vigils, essay contests, and public rallies, it is yet to be recognised by the state government as an official holiday to commemorate those killed.

What makes up public policy failures?

a) Lack of Participatory Policy-Making:

Instead of consulting different groups, the government decided to make Assamese the constitution’s only official language.

b) Neglect of Ground Realities:

Those in charge of policies did not take into account that nearly all people in Barak Valley spoke Bengali.

c) Over-centralisation of Identity Politics:

Putting a single language identity before all others in politics did not permit the government to support the state’s multicultural values.

d) Poor Crisis Management:

An excess of forceful reaction to peaceful protest is a sign that democratic crisis management is lacking and that officials rely too much on coercion.

Cities in other Indian states face the same challenges

The Barak Valley Language Movement holds significance across India, particularly in regions rich in cultural, tribal, and linguistic diversity. Recent debates over the imposition of Hindi in schools have underscored tensions between regional languages and Hindi. In Tamil Nadu, the anti-Hindi agitations of the 1960s remain a powerful example of people rallying to protect their language. Similar efforts continue in Northeast India, where communities strive for greater recognition of local languages. In Jammu and Kashmir, protests have emerged against proposals to phase out Urdu in favour of Hindi and English, further fueling concerns over linguistic marginalisation.

Key Lessons

States must recognize that one-size-fits-all language policies are incompatible with India’s pluralistic character. Articles 29 and 30 of the Indian Constitution, which support the cultural and educational rights of minorities, must be adhered to in letter and spirit.

Engaging in dialogue and building consensus with communities is essential to ensure that cultural decisions unite rather than divide people, fostering mutual trust. Preserving India’s rich linguistic diversity depends on actively promoting regional languages in education, media, and public services.

Outcome: What Happens When Diversity Is Neglected

Ignoring a nation’s linguistic and cultural diversity leads to conflicts like those witnessed in the Barak Valley. What could have been a peaceful negotiation between states turned into a crisis due to top-down decision-making.

As India navigates the complexities of its vast diversity- both a strength and a challenge—this episode underscores the need for policymakers to balance national cohesion with respect for all communities while shaping the nation. When language is valued, it becomes a force for unity, but when imposed, it creates division. India’s unity will be strengthened not by uniformity, but by embracing and celebrating its rich diversity.

References:

- Guha, Amalendu. “Planter Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle & Electoral Politics on Assam, 1826–1947. Tulika Books, 2006.” https://cup.columbia.edu/book/planter-raj-to-swaraj/9789382381341

- Baruah, Sanjib. “India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.” https://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/13615.html

- “Barak Remembers Language Martyrs.” The Times of India, 20 May 2025. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- “The Tragedy of 19 May 1961: When 11 Bengalis Lost Their Lives.” OpIndia, 19 May 2020. https://www.opindia.com/2020/05/barak-valley-language-movement-19-may-1961-bengali/

- “Bengali Language Movement (Barak Valley).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bengali_Language_Movement_(Barak_Valley)

- “Language Movement.” Barak Human Rights Protection Committee. http://bhrpc.in/language-movement

- “Assam’s Barak Valley Celebrates 62nd Year of ‘Language Movement’; CM Pays Homage.” Hindustan Times, 20 May 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/barak-valley-celebrates-language-movement-62nd-anniversary-101684571348578.html

- “Silchar, 19 May 1961: When Indians Braved Bullets for ‘Bangla’.” The Statesman, 19 May 2023. https://www.thestatesman.com/india/silchar-19-may-1961-indians-braved-bullets-bangla-1503180160.html

- Nandy, Mridul. “Language Movement in Barak Valley, 19 May 1961: An Era of Brave Bengali Revolution.” Mridul Nandy’s Blogs, April 2012. http://mridulnandy.blogspot.com/2012/04/language-movement-in-barak-valley-19.html

- “Bengali Language Movement in Barak Valley.” Abhipedia. https://abhipedia.abhimanu.com/Article/IAS/MjM5NTEy/Bengali-Language-Movement-in-Barak-Valley-Assam-IAS

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are of the author solely. TheRise.co.in neither endorses nor is responsible for them. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.

About the author

Souzatya Dutta is a student of Politics and International Studies at Pondicherry University. His academic and writing interests focus on identity politics, cultural rights, and public policy in India. He is passionate about making lesser-known histories visible and contributing to thoughtful conversations on diversity and constitutional values.

Pingback: Development Diplomacy: The South’s Investment Race and the Politics of Progress - TheRise.co.in