Threats to the region’s wildlife were intensifying, with new challenges emerging, particularly those linked to the impacts of climate change. For centuries, the institution of Mahakal had helped elephants endure in the Dooars. But today, that alone may not be enough to shield them from the complex and growing challenges they face.

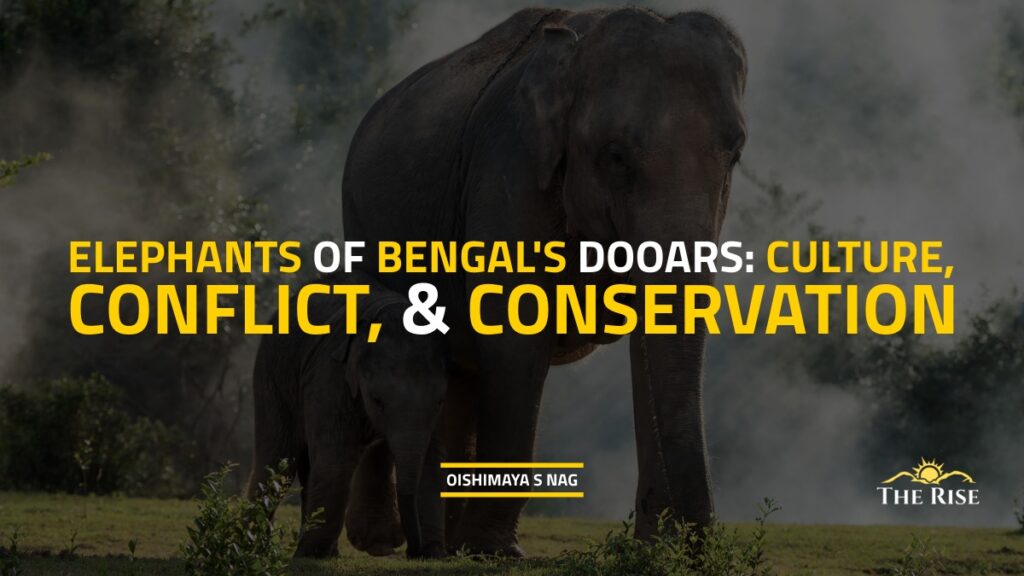

As our safari jeep drove through the dense, lush, and layered forest of the Gorumara National Park in the Dooars region of West Bengal, my eyes constantly scanned the surroundings in search of the ruler of this land – the majestic Asiatic elephant. This year, the monsoons had been particularly heavy, with sporadic rainfall continuing into November, the month of my visit. Hence, the foliage was exceptionally thick, offering little insight into the mysterious, wild world that flanked the road on either side. The forest appeared unusually quiet that day, and we were unable to catch a glimpse of the forest’s star resident.

“Look out for them in the village where you are staying, Madam,” my driver, Raghunath, informed me as we returned to the hotel at the end of the safari, a little disappointed. “It is the paddy (rice) harvest season, and the elephants are entering the village almost every day to feed on the crop,” he said.

Although it meant there was a fair chance of spotting the gentle giant, it was not really good news. The presence of elephants in human-dominated landscapes is always a major conservation concern. According to the 2025 nationwide census, the elephant population in West Bengal (North), which includes the Gorumara Wildlife Division, was found to be 676, an increase from the 488 elephants recorded in the 2017 census. For the first time, a DNA-based method was used in the census. DNA collected from elephant dung samples helped identify individual elephants, making the count highly accurate.

Despite the rise in numbers, the Elephant Status Report of the Wildlife Institute of India warned of severe habitat fragmentation in the region due to rapid developmental activities and proliferation of linear infrastructure facilities, such as roads and railways. Such conditions have restricted elephant movement, leading to human-elephant conflict situations.

As we exited the forest and drove down the highway, which cut through the forest and where vehicles moved at extremely high speeds, I understood the concern expressed in the report. Raghunath informed me that wildlife roadkills were quite common on this road, where speed limits were hardly followed.

Soon, we left the highway behind and entered a village road bordered by a patchwork of paddy fields, tea plantations, and small clusters of humble village homes. Raghunath pointed towards a paddy field and said, “Look, Madam, there you can see the footprints of an elephant in the mud.”

Indeed, massive depressions in the thick slush proved that elephants had entered the field. They had crossed the Murti River on the other side of the village and trampled across the field in search of food.

Raghunath informed me that elephants typically enter villages after dusk, when human movement is low. To guard their crops, villagers form patrolling groups in which men stay up all night to guard their fields from elephant invasions. They use powerful light beams or burst crackers to deter elephants from approaching. Sometimes, elephants also raid homes where grains are stored post-harvest. Even more tragic are the human fatalities that occur when accidental encounters startle the animals, prompting them to charge and trample anyone too close.

“So, people in the village must detest elephants, given that they raid their crops and cause economic losses to them and sometimes even human deaths?” I asked Raghunath in a concerned tone.

“No, Madam, not at all,” Raghunath shook his head in complete disagreement.

“The elephant is our God, Mahakal. We believe that it is our God feeding on our crops, and if an elephant kills one of us, we believe it is our fate. All we can do is pray to our Mahakal to appease the elephant to calm down and not vent its anger on us,” said Raghunath.

“We also believe that elephants remember those who have treated them well and reward them, while they punish those who have caused them harm,” continued Raghunath.

I was quite taken by surprise. I had recently visited the tiger shrines in the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve area of Maharashtra, where locals pray to the tiger to save themselves from attacks. I was unaware that a similar cultural institution existed here in the Dooars for the elephant!

“I will take you to the Mahakal Temple tomorrow morning while going to the watch tower safari gate,” said Raghunath.

Amazing! An elephant shrine here, just like the tiger and leopard shrines of Maharashtra. I couldn’t wait until morning to visit the place.

Back at the hotel, I began researching the Mahakal cultural institution of the Dooars, and a published research paper authored by the renowned wildlife scientist Dr Vidya Athreya and other researchers appeared in my search results. The paper revealed how some believers of the Mahakal rejected the compensations provided to them by the forest department for crop raids by elephants. According to these believers, their crops served as an offering to God and taking a monetary grant in return would be to disrespect their elephant God. They also believed that if the elephant visited their field, it would result in higher yields the following year. In another paper published by Dr Athreya and other authors, the team demonstrated how the cultural institution of the “Big Cat God” or Waghoba enabled local indigenous communities in Maharashtra to coexist with leopards and tigers for thousands of years. Thus, it seemed to me that the Mahakal and the Waghoba are India’s indigenous conservation strategies.

The next day, we started our safari early in the morning. As promised, Raghunath stopped the jeep at the Mahakal shrine. Right beside the highway, a few steps down led to an opening in the forest. Three statues of elephants, cut out of rock, stood there, along with rock sculptures of many other deities, all decorated with vermilion and decked with garlands, holy flags, and incense. Some members from the local community were visiting and praying to the Mahakal deity, and I became a silent observer of this unique faith system.

The forest safari that followed was thrilling. Two leopards hiding in the bushes, a pair of barking deer crossing the forest path, a wild boar, a herd of spotted deer, and several other animals revealed themselves along the way. The views from the watchtowers were mesmerising, offering a sweeping glimpse of why the Dooars captivates so many visitors. Yet, even on this safari, the elephants remained out of sight.

On the way back, a large multi-story residential complex near the village caught my eye. I asked Raghunath about the people who lived there.

“These belong to people from Kolkata and other big cities,” he explained. “They buy apartments here and visit occasionally to escape the din and bustle of city life.” He added that more such large projects were coming up across the area.

I understood that this is an emerging threat to the elephants, who had already lost vast tracts of forest and grassland habitat to agriculture and expanding rural settlements. Now, people from cities are introducing urban-style housing infrastructure, featuring tall, guarded walls, to elephant territory, which further impedes their movement. If only people would think more sensibly before making such choices. I sighed.

Another major change in the Dooars is the rapid spread of tea plantations. Alongside paddy fields, I saw tea gardens of every scale, from tiny plots owned by villagers to sprawling estates run by major tea companies. Even the buffer zone of Gorumara National Park was dotted with tea plantations managed by members of nearby villages.

Tea, I learned, is quickly replacing paddy and other crops in the Dooars for two reasons: elephants do not raid tea fields, and it earns farmers far more profit. However, this shift has introduced a new problem in the area – an increase in human–leopard conflict, as leopards, suffering from the loss of their natural habitat, are forced to adapt to the altered landscape.

Leopards find tea plantations to be ideal shelters and have even begun breeding and raising cubs in this human-created habitat. These leopards have taken to hunting down easier prey, such as village livestock and domestic dogs. Sometimes, they also attack and kill tea garden workers when sudden encounters occur. With the expansion of tea gardens, the frequency of such attacks is expected to increase.

Adding to the growing woes of the wildlife in the Dooars region is the looming threat of climate change. Rainfall patterns have changed in the area, with erratic variations hurting crop yields. Warming temperatures pose a significant challenge to the local tea industry. Not just tea, but other crops are also affected. As people suffer greater economic losses due to such threats, their tolerance for wildlife might decrease.

It is therefore vital to implement urgent conservation interventions in the Dooars of West Bengal to secure the survival of its elephants and other wildlife, and to ensure a stable and prosperous life for the region’s people.

With all these thoughts swirling in my mind, I returned to the hotel and settled down with a hot cup of tea at the restaurant, when suddenly, a staff member called out to me.

“Please come to the terrace quickly, Ma’am,” said Bhola, the hotel staff member.

I quickly climbed the stairs to the terrace with Bhola, who pointed toward the distant river. I raised my binoculars, thankfully still with me from the safari, and there, on the opposite bank, stood a lone elephant. At last, the darshan of the Mahakal! I managed to capture a few quick photographs before the great being disappeared into the darkness of the forest beyond the river.

I left the Dooars that evening with mixed feelings. The place still abounded in natural beauty, diverse wildlife, and kind-hearted locals who believed in living in harmony with nature, offering hope for the future.

However, threats to the region’s wildlife were intensifying, with new challenges emerging, particularly those linked to the impacts of climate change. For centuries, the institution of Mahakal had helped elephants endure in the Dooars. But today, that alone may not be enough to shield them from the complex and growing challenges they face. Policy-level interventions that secure habitats, modern technologies that prevent road and railway collisions, and stronger community awareness about coexisting with wildlife are all essential steps if we hope to create a safer future for these gentle giants.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author solely. TheRise.co.in neither endorses nor is responsible for them. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.

About the author

Dr. Oishimaya Sen Nag is a wildlife conservation storyteller and conservation science communicator. She is also the Senior Editor of WorldAtlas. After completing a PhD in Parkinson’s Disease research, she transitioned into the field of wildlife conservation. She travels across India to collect conservation stories and has written scores of articles on wildlife conservation that has been published in various national and international publications.