Despite decades of educational reform, India still lacks comprehensive research on inclusive TLMs (Teaching Learning Materials) and pedagogical strategies for visually impaired learners. The RPWD Act (2016) mandates free education for every child with benchmark disabilities in special schools. However, the Act does not ensure that these schools are equipped with the materials and infrastructure necessary for quality and subject-specific teaching.

“Ma’am, I am interested in learning geography, but I couldn’t learn it properly in school because I couldn’t see the diagrams and pictures in the textbooks, nor could I understand the visuals used in class.”

This reflection from a partially visually challenged student in one of Saswati’s classes led us to re-examine the way geography is taught. Without this honest expression, we may never have fully realised the need to design an inclusive learning space for visually challenged students.

At the Geography Lab of Azim Premji University, one of our ongoing projects focuses on developing tactile materials and models to facilitate the learning of various geography concepts. Although this work initially aimed to enrich the learning experiences of visually challenged learners, we soon realised that such tactile materials also enhance learning for sighted students. Our present focus, therefore, is to create teaching–learning materials (TLMs) that make geography classes truly inclusive—transforming abstract geographical concepts into experiential and tangible learning experiences.

The Myth of Inclusive Learning Spaces

Teachers across India handle classrooms of students with diverse abilities. As Belay and Yihun (2020) observe, “it is difficult to use a single method for teaching because students learn differently; a single method does not satisfy the needs of all students.”

Despite policy commitments, truly inclusive schools remain rare in India. “Special schools,” though well-intentioned, are often unaffordable for many families. As a result, exclusion of children with different abilities—particularly those with visual impairments—remains widespread. To understand these challenges, we discuss two key aspects:

- Understanding the meaning of visual impairment.

- The perception of “difficulty to learn” versus “inability to learn.”

Understanding Visual Impairment

According to Maindi (2018), visual impairment refers to the loss of vision even when an individual wears corrective lenses. The World Health Organization (2019) defines it as a condition involving significant limitation of visual functions—including contrast sensitivity, colour vision, visual acuity, and visual field—caused by disease, trauma, or congenital conditions that may or may not be treatable.

From an educational perspective, learners with visual impairments are generally categorised into two groups:

- Those who use print as their educational medium.

- Those who rely on Braille.

The major challenges for such learners in India stem from limited awareness or training of teachers and a lack of suitable tools, resources, and institutional support to make classrooms genuinely inclusive.

Difficulty to Learn vs. Inability to Learn: A Perception Problem

A persistent social misconception equates visual impairment with an inability to learn. Many teachers and parents believe that visually impaired students cannot learn using visual aids and therefore exclude them from certain classroom activities. As Dias et al. (2010) observe, in some schools for visually impaired learners, illustrations and figures are systematically omitted from textbooks, ranging from shapes in early grades to maps in higher grades.

This exclusion limits students’ conceptual understanding. If such practices continue, the learning gap will persist indefinitely. The question then arises: How can we make inclusive learning a reality rather than a myth?

Teachers working with visually impaired students face varied challenges depending on the classroom context. Those in specialized schools address different degrees of visual impairment and must adapt their pedagogy accordingly. Teachers in inclusive classrooms—where a few visually impaired students learn alongside sighted peers—face the dual challenge of catering to both groups.

Key questions emerge:

- Should visual aids still be used?

- If yes, how can they be made accessible?

- What methods and materials can support both groups effectively?

Barriers in the Learning Process

Students with visual impairments lack visual experiences that sighted peers take for granted. As Tipi et al. (2023) and McDonald & Rodrigues (2016) note, school learning often relies heavily on visual media, which includes illustrations, maps, and written text. Without alternative sensory experiences, visually impaired learners struggle with comprehension and engagement.

Despite decades of educational reform, India still lacks comprehensive research on inclusive TLMs (Teaching Learning Materials) and pedagogical strategies for visually impaired learners. Halder (2022) identifies “parental reluctance, lack of teacher support, and absence of enthusiasm” as key barriers. Yet, where one sense is limited, others—touch, hearing, spatial perception—can and should be engaged to enable meaningful learning.

Perceptions Leading to Inappropriate Practices

In many classrooms, auditory learning becomes the only mode of instruction for visually impaired students. Teachers often read aloud instead of providing tactile or experiential alternatives. As Kapur (2018) explains, the pressure to complete the syllabus—especially in large classrooms—forces teachers to prioritise coverage over comprehension. When teachers lack the training or confidence to adapt lessons, they skip complex visual topics such as maps or the solar system.

Also Read: The Erosion of Geographical Literacy among Children in India

This overreliance on rote memorisation disadvantages visually impaired learners even further. Sighted students may compensate through visual references in textbooks, but visually impaired learners are deprived of any conceptual anchor. Without tactile or alternative sensory input, geography becomes a subject of memorised facts rather than meaningful understanding.

Policy Framework and the Way Forward

Both the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD, 2016) and the National Education Policy (NEP, 2020) envision an inclusive and equitable education system.

The RPWD Act (2016) mandates free education for every child with benchmark disabilities (including blindness and low vision) between the ages of 6 and 18 in a neighbourhood or special school. However, the Act does not ensure that these schools are equipped with the materials and infrastructure necessary for quality, subject-specific teaching—particularly in subjects like geography, which rely heavily on spatial understanding.

Similarly, NEP 2020 states that schools and school complexes will be supported to provide all children with disabilities the necessary accommodations and mechanisms for full participation in the classroom (Government of India, 2020). To realise this vision, investment in infrastructure, teacher training, and affordable TLMs is essential, along with active community and parental involvement.

Effective inclusive classrooms can utilise a range of TLMs:

- Audio and audiovisual materials

- Large-print and Braille charts

- 3D and tactile models

- Assistive technologies and devices

However, access remains a challenge. As Dias et al. (2010) highlight, tactile printers, embossed maps, and Braille books are prohibitively expensive for many schools, especially government institutions. Civil society organisations have helped bridge this gap, but sustained systemic support is needed.

One promising approach is the “Touch–Listen–Learn” model, which uses tactile graphics in combination with auditory feedback through mobile applications (Tipi et al., 2023). This dual-sensory approach enables learners to explore content independently and at their own pace.

From Waste to Wonder: The Geography Lab Initiative

At the Geography Lab, Azim Premji University, we design and build tactile models that make geography concepts accessible through touch and feel. We aim to support both sighted and visually challenged learners in understanding complex spatial concepts.

The models are made from waste and low-cost materials, combining sustainability with inclusivity. This approach offers three key advantages:

- Promotes inclusive learning for all.

- Encourages environmental sustainability by reusing materials.

- Ensures affordability and replicability across diverse school contexts.

Each model captures distinct textures and forms, representing physical landscapes or spatial relationships. Through iterative design, feedback, and refinement, we continue to make these models more effective and accessible.

Selected Models

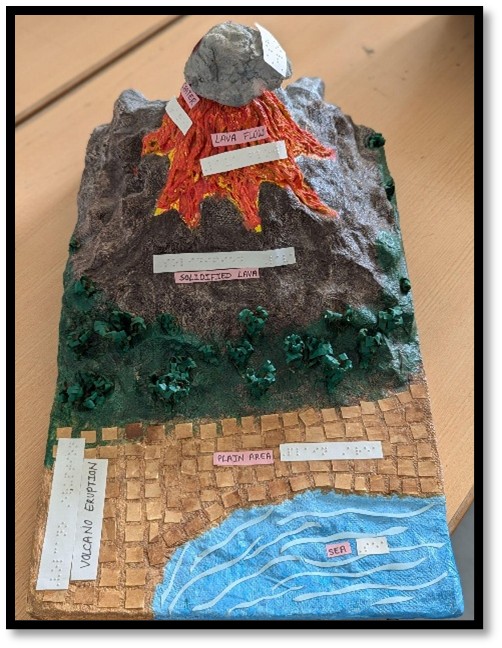

Figure 1 is the model showing the structure of a volcano, which shows an opening in the Earth’s crust through which molten material flows onto the surface. The model can be used in the classroom to help students understand and visualise the layers of Earth and how volcanic activity occurs.

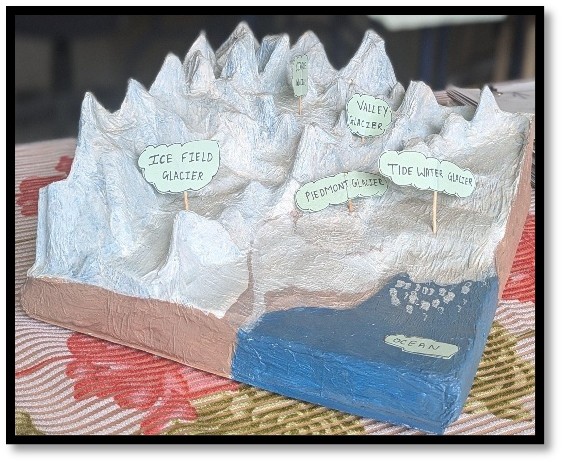

Figure 2 shows a model depicting different types of glaciers, such as ice field glaciers, valley glaciers, tidewater glaciers, piedmont glaciers, etc. This model helps students understand and feel the shape and flow of the glaciers, enabling a more tangible grasp of their structure and movement.

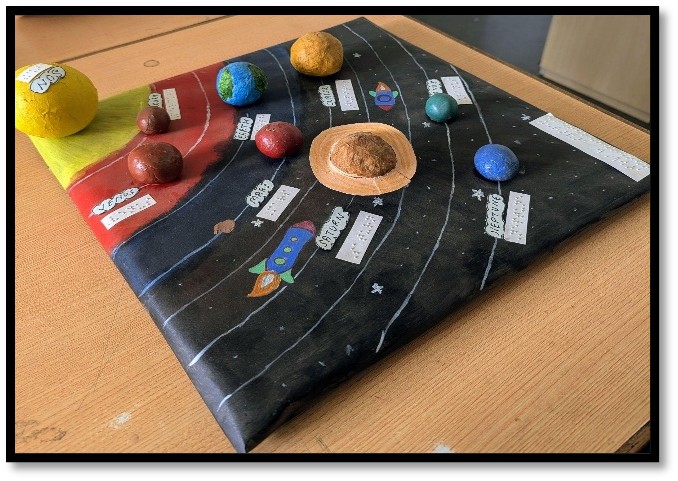

The model in Figure 3 shows the structure of the solar system, consisting of the Sun and the eight planets. The planets move around the Sun in fixed paths. This model helps students understand the relative positions of the planets with respect to the sun.

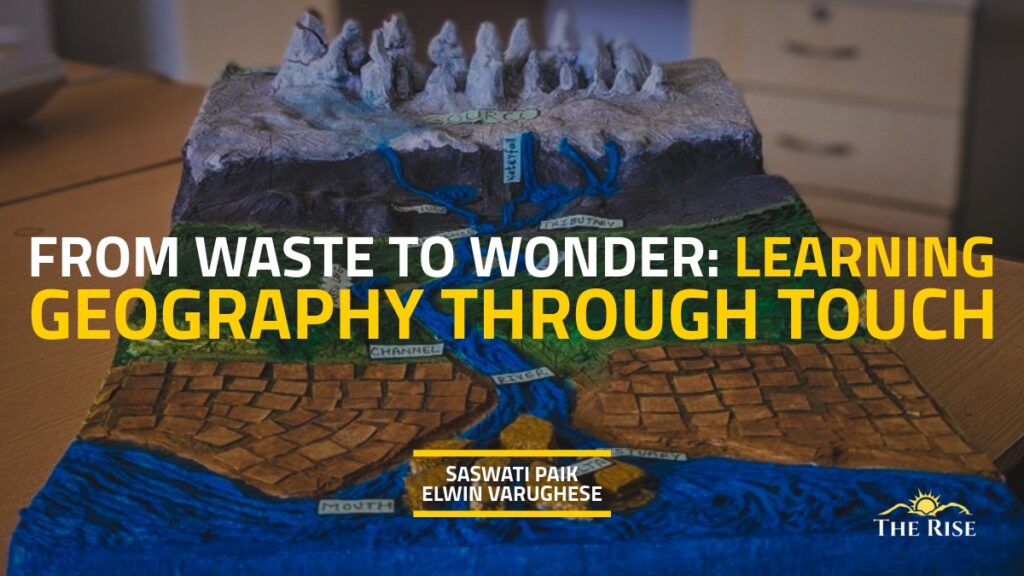

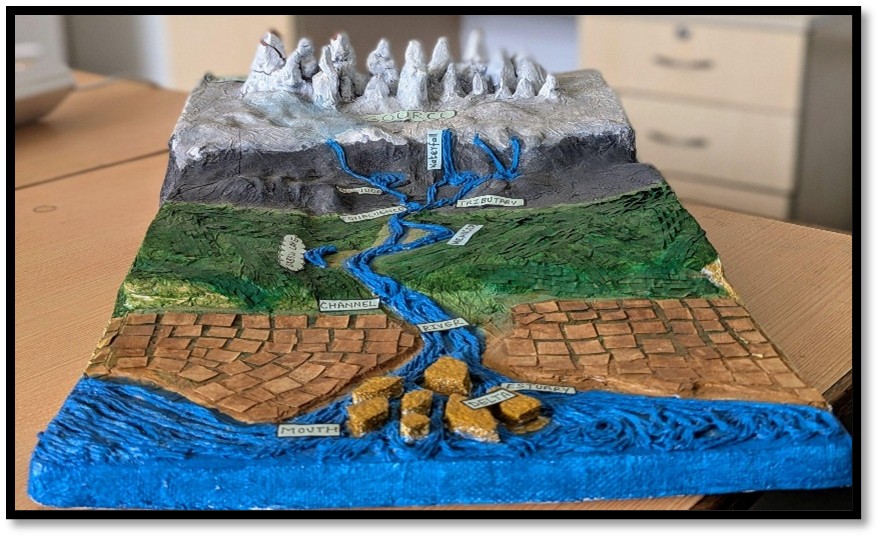

Figure 4 shows a model of how a main river, along with its tributaries, looks. The main elements of the river system are the main river, tributaries, source, mouth, and drainage basin. The model helps students to visualise and understand the features of the river system. It also helps create curiosity within students to probe further understanding.

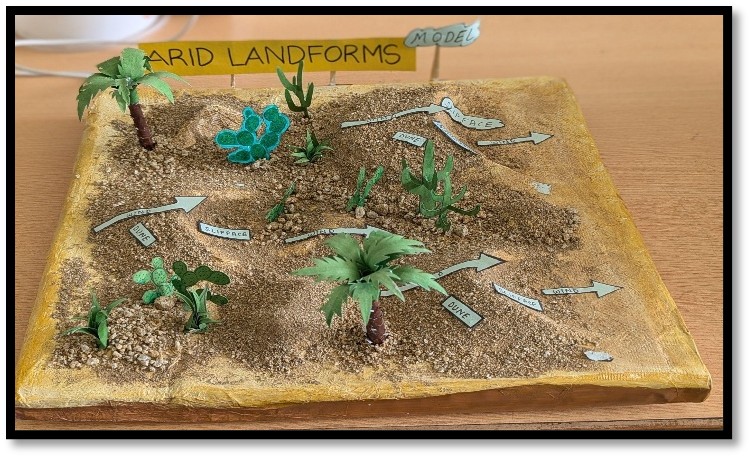

The model in Figure 5 illustrates a dune, which is a hill or ridge of loose sand formed by the action of wind in a desert. This model provides a visual and tactile representation of a dynamic natural feature that many may never see in their lifetime. It makes the abstract features of the desert more concrete and accessible.

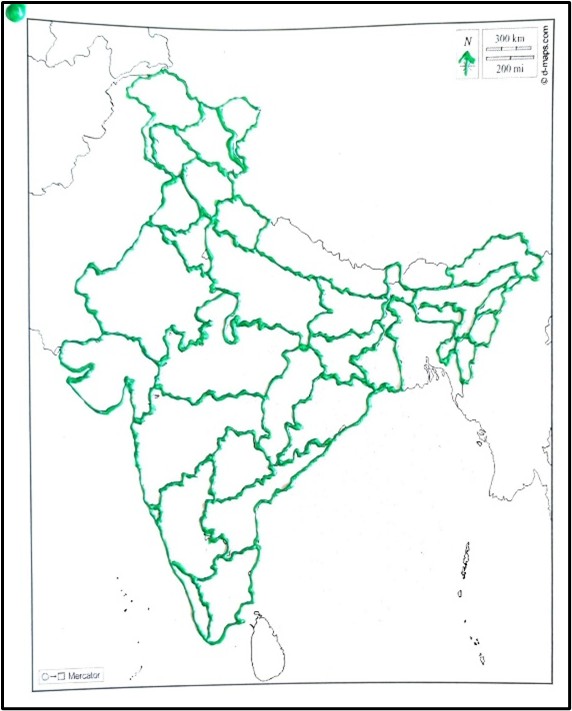

Figure 6 shows a tactile map of India. Many visually impaired students cannot access maps in their textbooks, and teachers often skip teaching maps altogether. Therefore, visually impaired students find it difficult to perceive the outlines of geographical areas. Tactile maps enable students to feel and understand boundaries, ultimately helping them visualise and comprehend spatial relationships more effectively.

These models demonstrate that inclusive education can also be creative, sustainable, and low-cost. Our lab welcomes learners and educators who wish to explore geography through sensory experience and inclusive pedagogy.

Ultimately, our goal is to contribute to a culture of inclusion in geography education, where no learner is left behind and every learner is encouraged to imagine, explore, and understand the world through their own senses.

References

- Belay, M. A., & Yihun, S. G. (2020). The Challenges and Opportunities of Visually Impaired Students in Inclusive Education: The case of Bedlu. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 4(2), 112–124.

- Dias, M. B., Rahman, M. K., Sanghvi, S., & Toyama, K. (2010, December). Experiences with Lower-cost Access to Tactile Graphics in India. Proceedings of the First ACM Symposium on Computing for Development, 1–9.

- Halder, I. (2022). Learning School Geography by Visually Impaired Learners: Problems and Prospects. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts.

- Kapur, R. (2018). Challenges experienced by Visually Impaired Students in Education. Unpublished paper, ResearchGate.

- Maindi, A. B. (2018). Challenges faced by Students with Visual Impairments When Learning Physics in Regular Secondary Schools. International Journal of Education, Learning and Development, 6(9), 38–50.

- McDonald, C., & Rodrigues, S. (2016). Sighted and Visually Impaired Students’ Perspectives of Illustrations, Diagrams and Drawings in School Science. Wellcome Open Research, 1, 8.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. (2016). The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (No. 49 of 2016). The Gazette of India.

- Ministry of Human Resource Development. (2020). National Education Policy 2020. Government of India.

- Tipi, S. K., Zorluoglu, S. L., Uçus, H., & Külekçi, H. (2023). Teaching Concepts to Students with Visual Impairments: Touch–Listen–Learn Model. Journal of Inquiry-Based Activities, 13(2), 151–163.

- World Health Organization. (2019). World Report on Vision. www.who.int

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors solely. TheRise.co.in neither endorses nor is responsible for them. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.