Biodiversity or wildlife-related conflicts are often described as situations where wildlife comes into conflict with humans over common resources. However, in many situations, particularly in those where conservation organizations are active, conflicts take the form of disputes between different stakeholder groups over wildlife management goals or priorities, and it is increasingly being acknowledged. Recent research shows that the development of conservation management schemes is affected by a multifaceted range of criteria and this has implications for the design of such schemes, and the way in which their aims are communicated to those affected and executed. There is now a growing awareness amongst conservation biologists that sociological and psychological approaches are often required to achieve a realistic understanding of such issues. Local communities are carrying a very heavy burden of conservation, while elites have the pleasure of enjoying the wilderness and wildlife, resulting in the cost-benefit ratio of conservation being strongly skewed in favour of tourism companies, national governments, and the international conservation community. Compensation and enhanced assistance to the locals should be regarded as a payment for ecosystem service they were generationally safeguarding and contributing towards its sustenance.

He had been pushed to the periphery, transformed from a beaming man-eater into a captured animal. Its authenticity was questioned, which eventually led to them being pushed to the periphery of the burgeoning punk scene or sententiously with the social problems pushed to the periphery. But the MDT-23 tiger would not be pushed to the periphery or turned into a sidebar. On 19 July 2021, around 02:00 pm a human was killed by a tiger at Ninganalolli hamlet of Muthuguli village in Mudumalai Range limits of Mudumalai Tiger Reserve (MTR) Core area. The deceased was identified as a male aged 49 years from Ninganakolli hamlet. The villagers staged a protest against the straying tiger, demanding that the tiger be captured immediately and the villagers be given protection from further damage or loss of human life. It may be noted that incidentally, the whole of Muthuguli village is an identified village for relocation.

After completion of formal procedures and handing over of the body to the family and disbursement of the relief, instructions were issued by the Deputy Director, MTR to the Forest Range Officer, Mudumalai Range, to fix camera traps in and around the human kill location to establish the identity of the Tiger. The bushes around the village periphery were cleared out to facilitate monitoring the movement of the tiger straying into human habitations, and a public addressing system was installed to continuously alert villagers on tiger movement. On the same night, the straying tiger was captured in the camera traps fixed at different locations and was identified as the resident MDT – 23 male tiger of MTR from the database at Tiger Monitoring Centre of the Tiger Reserve.

Since 2018, the MDT – 23 had exhibited cattle lifting behaviour and there was also a second human kill – a woman aged 50 years from Kurumbarpadi hamlet of Singara village in the limits of Singara Range, Masinagudi Division of MTR, in 2020. Therefore, further instructions were given to continue the monitoring of the tiger’s movement and to ascertain whether it continues to stray back in and around human habitation or remains within the forest area, based on which further course of action would be taken as per the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) protocol. Additional camera traps were fixed in the periphery of Muthuguli village and around 2-3 km in its periphery to monitor the tiger movement. Tracking staff was deployed around the area, and bushes were cleared to increase visibility and for the safety of villagers. Meanwhile, the details of the straying tiger were informed to the District Collector and Superintendent of Police of Nilgiris.

On the night of 20 July 2021, the patrol sighted the tiger moving outside the Muthuguli village limits. The next day there was an incident of cattle lifting and killing by an unidentified tiger in Devan Tea Division of Devarsolai estate of Gudalur division limits, about 1 km from the MTR Forest boundary. The location of the cattle kill was about 6-7 km from the Muthuguli village, where the human kill incident occurred. Local villagers drove away the tiger immediately after the cattle kill and the carcass was buried. Meanwhile, the Gudalur Forest Division staff also sighted the tiger.

To ascertain the identity of the tiger and monitor its further movements, in coordination with Gudalur Range staff, those from Nellakottai and Mudumalai Ranges of MTR were instructed to inspect the location and fix the camera traps in and around the cattle kill location. On 22 July 2021, two cattle calves were attacked and killed in the Devan Tea estate area. The tiger left the first calf carcass because of disturbance by the public; however, the second calf was dragged into the bushes and was consumed partially. The location of the 2nd and the 3rd cattle kill was about 300 meters away from the 1st, and therefore instructions were issued to deploy more camera traps in and around the 2nd and the 3rd kill locations. On 23 July 2021, from the camera traps, it was identified that the tiger was the same one that had killed cattle on 19 July 2021. The tiger was located just about the same area and it was found that it had eaten the cattle carcass completely. The tiger was not captured in the camera traps laid in the Devan Tea Estate, but was captured in the camera traps near the approach road to Bospara-Muthuguli village of Mudumalai Tiger Reserve limits.

Profiling MDT – 23

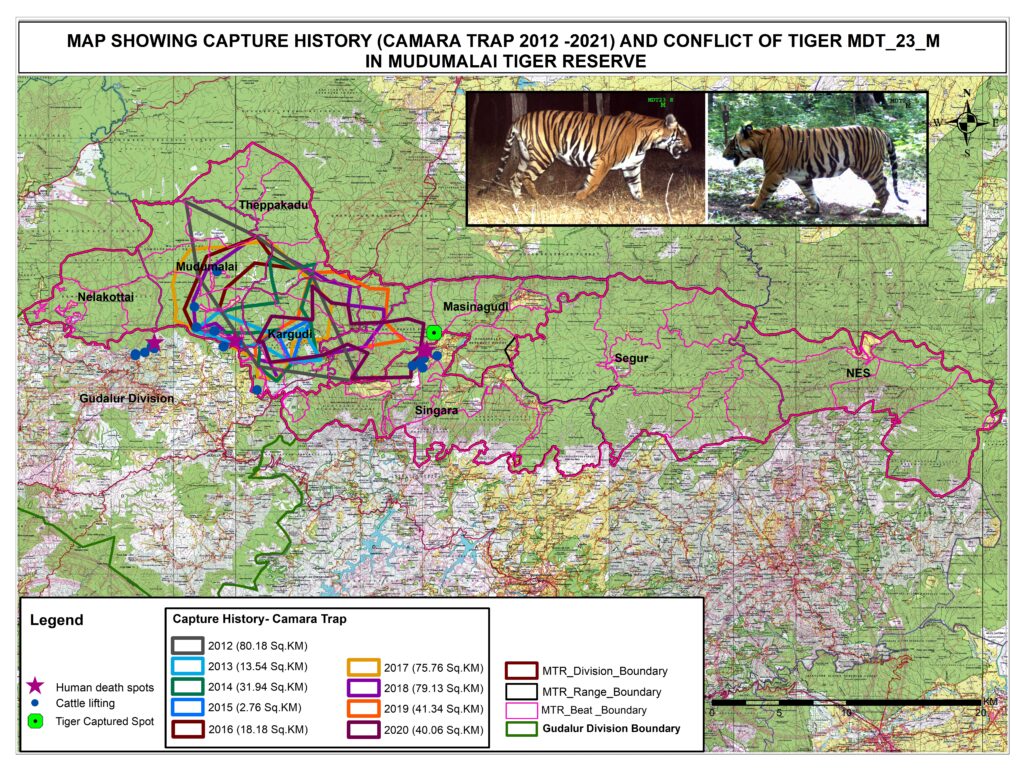

MDT – 23, the young male tiger, was first recorded in 2012 through a camera trap from the Core area of MTR, and it was assessed that it might be around 2-3 years old based on the camera trap images and features. Thereafter, this tiger was regularly captured in camera traps in MTR and came to be considered a resident and one of the dominant male tigers of the Tiger Reserve Core area. The territory of this tiger is estimated to be around 129.50 sq.km of the core (Mudumalai, Kargudi, Theppakadu and Masinagudi). Most of the camera trap captures show that the home range of this tiger is within Mudumalai and Kargudi ranges. However, the tiger has been seen moving through the Theppakadu range (Imberallah, Kakkanallah and Circle Road beat) and the Masinagudi range (Morganbetta and Karadibetta beat). The average territory of this tiger is 41.81 sq.km with a minimum of 2.26 sq.km and a maximum of 80.18 sq. km. Since 2018, this tiger has had a routine behaviour of killing cattle in and around Mudumalai range village areas. It was reported that the tiger was involved in killing 20 cattle and 4 humans.

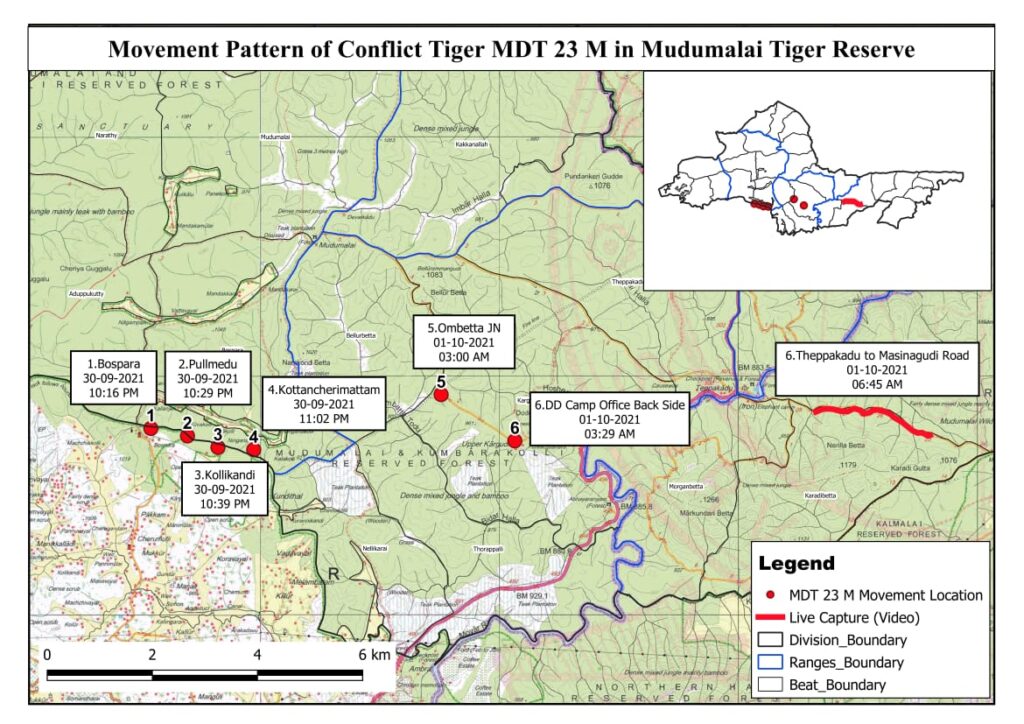

On 17 July 2019, near Nambikunnu village in the Mudumalai range of MTR a buffalo kill was reported. The following day, camera traps were fixed in and around the carcass location. From the camera trap images, it was confirmed that the tiger in question was MDT-23. The images showed that the tiger had a heavy injury in its right eye region, and later in 2020 after the cattle kill, a laceration on the left side of the nasal ridge was confirmed, indicative of intraspecific aggression. Further, it was also concluded that the age of MDT-23 maybe 12-13 years. In October 2021, it was observed that the tiger had an injury on the right side of the body and left front leg. Later, camera traps were deployed in and around village boundaries of Mudumalai, Kargudi, Singara and Masinagudi ranges of MTR where the tiger movement was high. Without creating a panic situation among villages, the Forest Department created awareness about the tiger movement and the field staffs were instructed to monitor the tiger movements as per the guidelines of NTCA. After the human kill in Mayfield, the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests and Chief Wildlife Warden issued an order to capture the problematic tiger MDT – 23 and the operation was continued in MTR from 1st to 15th October 2021 and the tiger was captured at Uppukuzhi Elephant path of Gaviallah beat of Masinagudi Range of Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. The tiger was given first aid by the veterinary doctors, who reported that the tiger was weak due to a lack of food for the last few days. Later, the captured tiger was translocated to the rehabilitation centre at the Mysore Zoo in Karnataka. This is the first time a conflict tiger was captured alive in Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, and rehabilitated to control conditions.

Managing Biodiversity Conflicts

Biodiversity or wildlife-related conflicts are often described as situations where wildlife comes into conflict with humans over common resources. However, in many situations, particularly in those where conservation organizations are active, conflicts take the form of disputes between different stakeholder groups over wildlife management goals or priorities, and it is increasingly being acknowledged. This definition emphasizes the significance of actors’ perceptions of each other’s values and goals, and their roles and responsibilities in relation to the situation in question: thus, a conflict emerges due to actors’ attributions and interpretations of the situation, rather than as a direct consequence of competition over resources. Conflicts and disputes arising from predators and their impact on commercial or conservation interests have prompted research efforts, principally from an ecological perspective, focused on how such situations might be better managed or averted. Whilst undeniably important in defining the problem and for the development of wildlife management solutions, such studies often ignore the presence of social and economic factors that have an influence on which solutions are considered acceptable.

The various drivers of biodiversity change, their impacts, the mechanisms through which conflicts ensue and how those conflicts are being addressed, effectively or otherwise, have been widely studied. Their conclusions highlight the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to understanding such problems and finding sustainable solutions to them. This corresponds with evidence that even a combination of ecological and economic perspectives is often not sufficient given that conservation-related conflict may not arise only from differing economic or technical land-use objectives, but also from other complex factors such as psychological reactance, social identity, community aspirations and general societal perspectives about development. Recent research shows that the development of conservation management schemes is affected by a multifaceted range of criteria and this has implications for the design of such schemes, and the way in which their aims are communicated to those affected and executed. The need for participatory analysis and informed decision-making is now being recognized to be essential. It implies that the process in which stakeholders are involved is as important as the transparent use of robust ecological research findings while developing and executing strategies for the management of controversial environmental situations. There is now a growing awareness amongst conservation biologists that sociological and psychological approaches are often required to achieve a realistic understanding of such issues. If management actions are to be accepted by stakeholders and proved successful in setting and achieving their aims, then due consideration must be given to how such management will affect peoples’ lives and elements of their culture, identity, and relationship with the environment.

Also Read: Local Communities Key To India’s Wildlife Conservation

The need for participatory analysis and informed decision-making is now being recognized to be essential. There is now a growing awareness amongst conservation biologists that sociological and psychological approaches are often required to achieve a realistic understanding of such issues.

Along the line with the brief of biodiversity conflicts given above, we suggest distinguishing two different, but essentially related, dimensions of the actors’ views on the situation in question. That is (i) the perception of the direct stakeholders on how the natural resources are affected and its implications on their livelihoods, and (ii) the perceptions they have of their position in the debate and decision-making, and that of the other actors involved. Recently, research on the first dimension has been increasing, addressing, for example, the question of how individuals’ values shape their attitudes towards resource management in the contexts of National Park designation and livestock and carnivore management. Decision modelling and decision analysis have been undertaken with stakeholders both in order to better understand their perceptions of the ecological aspects of particular conflicts and to explore pragmatic approaches for finding solutions.

The public’s desultory attitude towards the MDT – 23 was again confirmed by the high level of representation, implying that they were much concerened about the issue at Gudalur. That was of some significance but the perception would remain that MDT – 23 is now peripheral for Mudumalai. This would be especially because the Forest Department officials chose to capture the tiger alive, during the period the MDT – 23 event took place. Thus, officials reinforced the idea that MDT – 23 had to be captured. Indeed, despite the denial of the public, wildlife officials have shown consistently high enthusiasm for the capture of MDT – 23. This has been particularly so during the past four months when they seemed to believe that the interests of the people demanded capturing MDT – 23 to reduce their woes in accordance with the policies. Further, for the locals, MDT – 23 provided a drive to stand together to collectively bargain so that they could get better protection from the animals of MTR. However, by the time the tiger was captured, new political, social and economic issues had emerged which posed new challenges to the MDT – 23 capture operation. At the same time, the operation remained stuck in old grooves, fearful of adopting supple and innovative ways to move forward. Capturing MDT – 23 had increasingly become ineffective in tackling the emerging challenges. There is also the question, not on the need to compromise and co-operate either the people or the park managers or others but to what extent, and if at all such compromises yield tangible results.

Also Read: Why India’s Wildlife Needs The Right Kind Of Media Attention?

Evidence of local communities’ displacement abounds highlighting the devastating effects of displacement by protected areas on peoples’ livelihoods through the ensuing loss of access to traditional resources and adaptive strategies, such as key forage resources for livestock in the Tiger Reserve.

Obviously, the MDT – 23 capture operation served the Forest department’s interests well. The challenge for the officials and field team of the Tamil Nadu Forest Department now lies in ensuring that as it goes up the ‘great power’ ladder it retains the support for the live capture of the tiger. It can only do so if the public and disadvantaged people feel that unlike the established great powers it will focus on mutual benefit in dealing with them and not be exploitative.

Who is to blame? Will the public help to solve the problem? Public syndicates may be advocating the capture of the problem animal. However, there is a need for understanding the underlying causes that lead to the capturing problem if it is yet to be solved forever, even with all the money spent and all the manpower effort. This underscores the point that if all the money spent on the massive, highly coordinated capturing effort in MTR cannot prevent the lifting of livestock, how much more difficult will it be to save the tiger by the departments that do not have access to this sort of funding? We need to understand first that, local people across MTR need to be moved out to create effective protected areas (PAs). Evidence of local communities’ displacement abounds highlighting the devastating effects of displacement by PAs on peoples’ livelihoods through the ensuing loss of access to traditional resources and adaptive strategies, such as key forage resources for livestock in the Tiger Reserve.

Also Read: Wildlife Biologists: A Case for Inducting Them for Scientific Management of Forests

Local communities are carrying a very heavy burden of conservation, while elites have the pleasure of enjoying the wilderness and wildlife, resulting in the cost-benefit ratio of conservation being strongly skewed in favour of tourism companies, national governments, and the international conservation community.

To make things worse, not only do the local communities not benefit from conservation but also they are confronted with the serious challenge of having to contend with conflict with wildlife. Marauding tigers and other carnivores kill people and their livestock are infected with wildlife-related diseases such as foot and mouth disease, only to be translated into receiving a pittance from the sale of livestock compared to regions where wildlife is absent. Thus, local communities are carrying a very heavy burden of conservation, while elites have the pleasure of enjoying the wilderness and wildlife, resulting in the cost-benefit ratio of conservation being strongly skewed in favour of tourism companies, national governments, and the international conservation community. As local people continue to be deprived by conservation policies and practices, they are angry because they see others appreciably benefiting from their resources, while they receive very little or nothing therefrom; they only witness the damage caused by wildlife to their livelihoods.

Wildlife can only be saved by implementing their protection in their natural habitats, and that means we have to work with local communities and not against them. This system believes that communities in parts of the world where most endangered species live are a problem that must be fixed, most often by acquiring traditional lands, establishing camps and other experiences for wealthy tourists, and employing gun-carrying guards to patrol the boundaries of parks and reserves. What would happen if these communities were asked for their opinions on how best to conserve the animals alongside which they have lived for generations? They might also ask for assistance to help buffer the impact of conflict on their livelihoods so that the loss of lives and their livestock killed by wildlife could be compensated. In fact, such compensation and enhanced assistance to the locals should be regarded as a payment for ecosystem service they were generationally safeguarding and contributing towards its sustenance; indeed from the perspective of scientific conservation and human welfare, this is a very justifiable and genuine demand.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are of the author solely. TheRise.co.in neither endorses nor is responsible for them. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited

About the author

Dr Vaithianathan Kannan is a Wildlife Biologist who has worked with Sathyamangalam Tiger Conservation Foundation Tamil Nadu Trust, Erode, Tamil Nadu, Bombay Natural History Society, Mumbai & AVC College, PG Research Department of Zoology & Wildlife Biology, Mannampandal, Tamil Nadu, and various other NGOs. He is a member of the IUCN/WI/SSC Pelican Specialist Group (Old World) and has a voluntary position within the Old World Pelican Specialist Group. His research interests are diverse largely related to Ecology, Biodiversity, Limnology, Mammalogy, Ornithology and Wetlands

Pingback: Illegal Wildlife Trade - TheRise.co.in