Over 70% of rural households have suffered losses due to wild animals. Leopards and Himalayan black bears account for most livestock attacks, while monkeys, porcupines, and wild boars ravage crops such as maize, apples, and vegetables. The damage is deep and personal. Crop losses at times reach 30% of annual yield, forcing families to abandon traditional cultivation. Many have stopped growing maize altogether.

Ganderbal — the serene gateway to Kashmir’s alpine paradise — lies between the Sindh River and the towering Himalayas, a district where beauty hides a growing tension. Beneath the calm of pine-scented mornings, a quiet struggle unfolds between villagers and the wild creatures that once shared this land.

“This land belongs to both of us, we share this land, not as conquerors, but as neighbours — each with a right to live and flourish,” says Abdul Rehman, a farmer from Kangan. “But now, it feels like both man and animal are fighting to survive, “he further added.

In recent years, forests have receded, villages have expanded, and the delicate balance between humans and wildlife has fractured. Every new house pushes the wilderness back — yet every shrinking forest brings it closer.

A Rising Tide of Encounters

Recent surveys conducted across Ganderbal reveal a disturbing pattern: over 70% of rural households have suffered losses due to wild animals. Leopards and Himalayan black bears account for most livestock attacks, while monkeys, porcupines, and wild boars ravage crops such as maize, apples, and vegetables.

Incidents have risen sharply, with human injuries increasing by nearly 30% in the last five years. The conflict peaks during May to August, when ripened crops attract wildlife to the edges of farmland.

“Every year it gets worse,” says Ghulam Rasool, a herder from Lar. “Bears come for maize, leopards for our sheep, and now even monkeys are not afraid. They walk across the fields like they own them. When humans and animals learn to live side by side, every encounter becomes a lesson in patience and care,” he further said.

When Forests Fade, Conflict Rises

Ecologists trace this turmoil to deforestation, habitat loss, and unplanned expansion. Once continuous green corridors, they have now been sliced apart by roads, fields, and settlements. Traditional wildlife routes have given way to farmlands and backyards.

Also Read: Black Bears in Kashmir’s Dachigam Are No Longer Hibernating: What Could Possibly go Wrong?

As the forest shrinks and food sources decline, animals now wander into villages in search of sustenance. “We cut their trees,” says Abdul Hamid of Sumbal Bala. “Now they come looking for what we took. Coexistence begins with respect: seeing the forest not as ours to take, but as theirs to inhabit,” he further added.

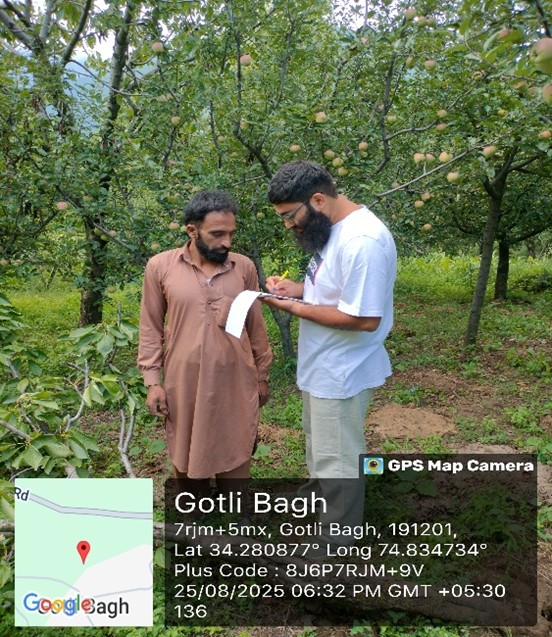

The Monkey Invasion: Fear in Gutlibagh, Sumbal Bala, and Baba Salina

At dawn in Gutlibagh, rooftops echo with the sound of scampering feet. Maize stalks bend under their weight, and kitchen gardens lie flattened. Among the new faces of this human-wildlife conflict, monkeys have emerged as the most persistent and unpredictable threat. In villages of Gutlibagh, Sumbal Bala, and Baba Salina, fear of monkeys dominates daily life.

“They came in through the window — took everything. When we tried to chase them, they bared their teeth. Even the dogs ran away,” Rafiqa Begum, a resident, recalls how a troop entered her home.

In Sumbal Bala, a village in Kangan tehsil of Ganderbal district, 40 km northeast of Srinagar, the story is much the same. Monkeys have learned the rhythm of human life — slipping into the fields when farmers are away, raiding shops after markets close, and even appearing on roads when children walk to school.

“We keep our children inside after noon,” says Firdous Ahmad, a local orchard keeper. “They throw stones at us, pull down drying clothes, and even open grain bags. They are no longer afraid.”

By evening, the villages grow tense. Women rush to collect laundry before dusk; farmers hurriedly build makeshift fences with wire and tin sheets. The line between safety and intrusion has blurred.

In Baba Salina, a village in Tulmulla block, Ganderbal district, around 25 km northeast of Srinagar, elders speak of monkeys entering school grounds and attacking fruit vendors. “It feels like the forest has moved into our homes,” says Amin Malik, whose orchard now stands half-destroyed. “They sit on trees watching us work — waiting for us to leave.”

The damage is deep and personal. Crop losses at times reach 30% of annual yield, forcing families to abandon traditional cultivation. Many have stopped growing maize altogether. “There’s no profit anymore,” sighs Shabir Ahmad from Gutlibagh. “Whatever grows, they take.”

Major Species Involved

Across Ganderbal, the conflict now stretches beyond monkeys. Each animal leaves its own distinct mark:

- Himalayan black bears raid maize fields and attack livestock.

- Leopards prowl near villages, preying on sheep and goats.

- Rhesus monkeys, once limited to forest edges, now dominate human spaces.

- Porcupines and wild boars destroy tuber and root crops at night.

- Wolves scavenge near garbage dumps, spreading waste across fields.

Yet among them all, monkeys have proven the hardest to deter — clever, adaptable, and fearless.

Life on the Forest Fringe

In the forest-bordering villages of Kangan, Lar, Gund, Wakura, Naranag, Gutlibagh, Sumbal Bala, and Baba Salina, daily life is shaped by vigilance. Nights echo with barking dogs and the crackle of fires lit to guard crops. Children are warned not to stray near the forest edge.

“We used to rest after work,” says Hafiza Begum from Naranag. “Now we spend the night listening — for bears, for leopards, for the noise on the roof.”

The fear is constant, but the resilience runs deeper. Villagers use noise, smoke, barbed wire, and torches as deterrents. Yet, as one farmer says, “Animals learn faster than humans forget. Whatever trick we try, they outsmart it.”

Socio-Economic and Psychological Impacts

The costs go beyond damaged crops. Losses of maize, vegetables, and livestock have reduced household income by up to 30%, pushing marginal families into debt. Children often skip school during peak wildlife activity, and migration toward nearby towns is rising.

The psychological strain is harder to measure. Sleepless nights, anxiety, and a sense of helplessness have become a part of daily life. “We used to sleep with our doors open,” recalls Mehraj Bano of Wakura. “Now even a dog barking at night makes us sit up.”

Ecological Roots of the Crisis

From an ecological perspective, this conflict mirrors a larger imbalance. Forest loss, unregulated waste dumping, and habitat fragmentation have disrupted natural food chains. Since 2000, Jammu and Kashmir has lost nearly 4% of its forest cover, leaving wild species with fewer resources.

With easier access to crops and garbage, animals like monkeys and bears are changing their behaviour — adapting to survive within human landscapes. “They are not wild anymore,” a villager said. “They are learning to live like us.”

A Fragile Coexistence

Despite growing fear, many villagers express compassion. “We are angry, but we understand,” says Abdul Hamid of Sumbal Bala. “If we destroy their home, where will they go?”

It is this awareness — this shared grief — that defines the conflict in Ganderbal. It is not merely a story of raids and losses; it is a story of two species forced to share a shrinking space.

On a late summer evening in Baba Salina, as the sun slipped behind the mountains, monkeys sat on the roofs, their silhouettes sharp against the red sky. Below, farmers hurried to gather what remained of their crops. In that moment, it was hard to tell who truly belonged — the people or the animals.

Conclusion

The story of Ganderbal is one of coexistence tested by change. From bears in the maize fields of Kangan to monkeys raiding homes in Gutlibagh and Sumbal Bala, each encounter tells of a landscape losing balance.

The people here are not fighting wildlife — they are fighting for the right to live alongside it safely. And as the forests shrink, both sides are drawn closer, unwilling participants in the same struggle for space, food, and survival.

In the end, the question is not who belongs, but how both can belong. “The forest remembers what we forget. When we take too much, it finds its way back — sometimes on paws, sometimes on hands that look too much like ours.”

Farhan Nazir is an intern at TheRise.co.in

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are of the author solely. TheRise.co.in neither endorses nor is responsible for them. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.

About the author

Farhan Nazir is a passionate wildlife enthusiast and Zoology postgraduate from the Central University of Kashmir. He is deeply committed to the study and conservation of nature. With a growing interest in biodiversity protection and ecological research, Farhan strives to blend scientific knowledge with on-ground action to safeguard fragile ecosystems and aspires to build a meaningful career contributing to wildlife conservation and environmental sustainability.